Ramsés III

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Contenido

Usermaatra-Meriamón Ramsés-Heqaiunu, o Ramsés III,[1] es el segundo faraón de la dinastía XX y el último soberano importante del Imperio Nuevo de Egipto. Gobernó de c. 1184 a 1153 a. C.[2]

Contenido |

Reinado [editar]

Política interior [editar]

Hijo de Sethnajt y casado con la reina Isis, continuó durante los treinta años que duró su reinado la labor iniciada por su padre, años antes, con el objetivo de poner fin a los momentos de anarquía vividos a la muerte de Siptah. Se dedicó a reorganizar la administración, toda vez que la paz y el restablecimiento del culto ya se habían encaminado, y la corrupción estaba desintegrando el país. Esta reforma viene determinada por la división administrativa en clases: funcionarios palaciegos, funcionarios provinciales, militares y trabajadores.

La economía del país se recuperó rápidamente gracias a la masiva llegada de tributos procedentes de las provincias asiáticas y nubias, y el comercio exterior entró en una etapa de plena vitalidad, llegando a tierras egipcias (especialmente desde el país de Punt) productos elegantes y caros que eran muy demandados por la sociedad. Este desarrollo económico motivó la recuperación de la fiebre constructora, levantándose nuevos templos y enriqueciéndose los ya existentes.

Política exterior [editar]

En su época desapareció el Imperio Hitita y otras entidades políticas menos importantes. Todo el Cercano Oriente se vio afectado, pero sin la resuelta intervención de Ramsés III, Egipto habría perdido su soberanía, como durante la época de los Hicsos. Ramsés III se marcó como objetivo alcanzar la preponderancia que Egipto había tenido anteriormente en la política exterior. La complicada situación que se vivía en Asia exigía una contundente respuesta por parte egipcia: los pueblos del mar habían acabado con el reino hitita, ocupando también Chipre y el país de Naharina. La provincia egipcia de Canaán recibía continuas incursiones de estos invasores que podían extenderse al mismo Egipto.

La zona del delta del Nilo había recibido una creciente inmigración atraída por una vida más fácil, por lo que durante los primeros años de su reinado, Ramsés III tuvo que hacer frente a dos grupos de pueblos indoeuropeos que se dirigían hacia el Delta. En el año octavo de reinado Ramsés se dirigió hacia Asia para hacer frente a los pueblos del mar. Se produjo una batalla naval en la desembocadura del Nilo, donde fue aniquilada la flota enemiga, y que junto al fortalecimiento de la frontera palestina fue suficiente para evitar la temible invasión de pueblos del mar, de la que difícilmente se hubiera recuperado Egipto, corriendo la misma suerte que el Imperio Hitita. La retirada de los pueblos del mar animó a Ramsés a retomar la colonización asiática emprendida por sus antecesores: Siria es recuperada en parte, tomando cuatro ciudades fortificadas, llegando incluso hasta las regiones del Eufrates. Pero la alegría por la victoria dura poco, ya que algunos años después las tierras de Canaán se perderán definitivamente.

La frontera libia también era peligrosa, tras una reorganización de los pueblos nómadas que habitaban en esa zona. En el undécimo año de su reinado, el ejército libio, deseoso de asentarse en el fértil territorio egipcio, avanzó hacia Menfis; en las cercanías de la ciudad se produjo la batalla, obteniendo el faraón la victoria. Los prisioneros fueron numerosos, y se entregaron como esclavos a los templos. Una vez suprimido este peligro, Ramsés se dirigió hacia Libia, donde se había producido una revuelta, posiblemente motivada por la imposición de un príncipe educado en la corte egipcia. Las tropas libias fueron derrotadas, obteniendo el faraón gran cantidad de prisioneros.

El Papiro Harris I: donaciones y expediciones [editar]

El Papiro Harris I fue editado por su hijo y sucesor, Ramsés IV y narra la crónica de los grandes donativos del rey: estatuas de oro y construcciones monumentales en varios templos de Egipto, en Pi-Ramsés, Heliópolis, Menfis, Atribis, Hermópolis, This, Abidos, Coptos, El-Kab y otras ciudades en Nubia y Siria. Registra también que el rey organizó una expedición comercial a la Tierra de Punt y ordenó extraer cobre de las minas de de Timna. Ramsés reconstruyó el templo de Jonsu en Karnak sobre la base de un templo más antiguo de Amenhotep III y completó el templo de Medinet Habu alrededor de su duodécimo año de reinado. Se decoraron los muros del templo de Medinet Habu con escenas de sus batallas navales y terrestres contra los Pueblos del Mar.

Construcciones de Ramsés III [editar]

Ordenó construir importantes ampliaciones en los templos de Luxor y Karnak, así como su templo funerario y el complejo administrativo en Medinet Habu, que están entre los más grandes y mejor conservados de Egipto. La incertidumbre en tiempos de Ramsés está presente en las grandes fortificaciones que construyó para protegerlo, y que ningún templo egipcio situado en el corazón de Egipto había necesitado antes. Allí se enterró, según la leyenda, a los miembros de la cosmogonía Hermopolitana, que recibieron culto hasta la llegada de los emperadores romanos.

Su tumba (KV11) en el Valle de los Reyes (Biban el-Muluk: Puerta de reyes) es de gran elegancia. Las escenas son fieles al arte egipcio tradicional.

Huelga en Deir el-Medina [editar]

La comunidad obrera de las tumbas reales (situada en lo que hoy conocemos como Deir el-Medina) desarrolló tres huelgas bajo el reinado de Ramsés III. Estas huelgas fueron las primeras documentadas en la historia de la humanidad, algunas de las cuales se recogen en un papiro que hoy se conserva en el Museo Egipcio de Turín. Las huelgas surgieron debido al retraso de las raciones alimenticias (en Egipto no existió la moneda acuñada hasta la dinastía XXX, en el siglo IV a. C.) que formaban parte de los sueldos de los obreros.

Los trabajadores llevaban más de veinte días sin recibir el sustento porque el gobernador de Tebas oriental y sus seguidores habían interceptado el envío. Cuatro meses después, el conflicto se reavivó. La entrega de alimentos se había demorado de nuevo, esta vez dieciocho días, y los obreros se vieron obligados a reclamar lo que era suyo, pero recibieron partidas insuficientes. Por esta razón interrumpieron el trabajo y se dirigieron al templo de Thutmose III en Medinet Habu, donde presentaron sus quejas, exigiendo que el propio rey fuera informado y proclamando: «Tenemos hambre, han pasado dieciocho días de este mes... hemos venido aquí empujados por el hambre y por la sed; no tenemos vestidos, ni aceite, ni pescado, ni legumbres. Escriban esto al faraón, nuestro buen señor, y al visir, nuestro jefe. ¡Que nos den nuestro sustento!». Los sacerdotes tuvieron que soportar duras negociaciones y huelgas intermitentes, y aunque no se conoce con seguridad cuál fue el desenlace de la situación sí sabemos que a partir de ese momento los robos en las necrópolis se incrementaron.

Conspiraciones [editar]

La tranquilidad se vio frustrada por las conspiraciones que se vivieron en el periodo final de la vida del faraón. Su visir Atribis intentó acabar con su vida, consiguiendo Ramsés escapar sano y salvo.

La segunda esposa real, Tiyi, lo intentará de nuevo al ver como su hijo era apartado de la línea sucesoria. A pesar de contar con el apoyo de altos funcionarios reales, el complot parece que fracasó ya que se descubrió en el último momento, deteniendo a los conspiradores y llevándolos ante la justicia. Poco tiempo después falleció Ramsés III, dejando el trono de Egipto en situación de gran debilidad, y aunque se especula que su muerte fue causada por los conspiradores, su momia no muestra evidencias de violencia.

Ramsés IV, hijo suyo y de la reina Isis, le sucedió y prefirió cerrar el asunto: con motivo de su solemne coronación, declaró la amnistía general pero no consiguió detener el deterioro del poder real.

Titulatura [editar]

| Titulatura | Jeroglífico | Transliteración (transcripción) - traducción - (procedencia) |

| Nombre de Horus: |

| k3 nḫt ˁ3 nsyt (Kanajt Aanesyt) Toro potente, de gran majestad |

| Nombre de Nebty: |

| ur ḥbu sd mi t3 tnn (Uerhebusedmitatenen) Grande en el Heb Sed como Ptah-Tatenen |

| Nombre de Hor-Nub: |

| usr rput mi itn (Userenputmiten) Repleto de años como Atón |

| Nombre de Nesut-Bity: |

| usr m3ˁt rˁ mr imn (Usermaatra Meriamón) Poderosa es la justicia (Maat) de Ra, amado de Amón |

| Nombre de Sa-Ra: |

| rˁ ms su ḥq3 iunu (Ramsés Heqaiunu) Engendrado por Ra, Señor de Iunu (Heliópolis) |

Otras transcripciones de su titulatura:

- Nombre de Horus: Anemnesumitemmerituefabatuefmihememra, Bityuermenuerbiautmejepetsuthorenef, Enhorserejmisaset, Kanajtdemehenutmenibuerpehtihorbauenqenu, Kapehtisejemjepeshnajtnebneruemtaujasutfenjutemehu, Kenaanesyt, Kendemejenumenibuerpehtihorbauenqen, Kenmaypehtinajtnebjepesheqasetiu, Kensusejkemetuserjepeshnajtsematejenu, Menajmenusehotepnebradyermenayefajut, Nebjaumitefra, Nebhabusedmitatenen, Sajaumiajtiubenfanjrejyt, Samenu, Sejempehtihedhefenudejnapusudemedhortjebauief, Tejenjau.

- Nombre de Nebty: Irimaatenpesdyetsehabraupera, Uerhebusedmitatenenpetpetejenuemiunuhorsetsen, Userpehtimitefmentuseksekpedyetdermitasen.

- Nombre de Hor-Nub: Anetyelemesutnetyerunetyerutqababetsen, Netyerimeperifemhotsujetjequretsebeqetenhorajti, Qenunebjepeshuiritashremeriefemsajaftiuf.

Notas [editar]

Enlaces externos [editar]

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Ramsés III. Commons

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Ramsés III. Commons- Titulatura, en Tierradefaraones.com

| Predecesor: Sethnajt | Faraón Dinastía XX | Sucesor: Ramsés IV |

Categorías: Faraones | Dinastía XX | Fallecidos en el siglo XII a. C.

Ramesses III

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Contenido

| Ramesses III | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Also written Ramses and Rameses | |||||

| |||||

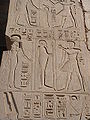

| Relief from the Sanctuary of Khonsu Temple at Karnak depicting Ramesses III | |||||

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |||||

| Reign | 1186–1155 BC, 20th Dynasty | ||||

| Predecessor | Setnakhte | ||||

| Successor | Ramesses IV | ||||

| Consort(s) | Iset Ta-Hemdjert, Tiye | ||||

| Children | Ramesses V, Ramesses VI, Ramesses VIII, Amun-her-khepeshef, Meryamun, Pareherwenemef, Khaemwaset, Meryatum, Montuherkhopshef, Pentawere, Duatentopet (?) | ||||

| Father | Ramses II | ||||

| Mother | Tiy-Merenese | ||||

| Died | 1155 BC | ||||

| Burial | KV11 | ||||

| Monuments | Medinet Habu | ||||

Usimare Ramesses III (also written Ramses and Rameses) was the second Pharaoh of the Twentieth Dynasty and is considered to be the last great New Kingdom king to wield any substantial authority over Egypt. He was the son of Setnakhte and Queen Tiy-merenese. Ramesses III is believed to have reigned from March 1186 to April 1155 BC. He was born approximately 1220 BC [1]. This is based on his known accession date of I Shemu day 26 and his death on Year 32 III Shemu day 15, for a reign of 31 years, 1 month and 19 days.[2] (Alternate dates for this king are 1187 to 1156 BC).

Contents |

[edit] Tenure and chaos

During his long tenure in the midst of the surrounding political chaos of the Greek Dark Ages, Egypt was beset by foreign invaders (including the so-called Sea Peoples and the Libyans) and experienced the beginnings of increasing economic difficulties and internal strife which would eventually lead to the collapse of the Twentieth Dynasty. In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea Peoples, including Peleset, Denyen, Shardana, Weshwesh of the sea, and Tjekker, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. Although the Egyptians had a reputation as poor seamen they fought tenaciously. Rameses lined the shores with ranks of archers who kept up a continuous volley of arrows into the enemy ships when they attempted to land on the banks of the Nile. Then the Egyptian navy attacked using grappling hooks to haul in the enemy ships. In the brutal hand to hand fighting which ensued, the Sea People were utterly defeated. The Harris Papyrus state

| “ | As for those who reached my frontier, their seed is not, their heart and their soul are finished forever and ever. As for those who came forward together on the seas, the full flame was in front of them at the Nile mouths, while a stockade of lances surrounded them on the shore, prostrated on the beach, slain, and made into heaps from head to tail.[3] | ” |

Ramesses III claims that he incorporated the Sea Peoples as subject peoples and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is no clear evidence to this effect; the pharaoh, unable to prevent their gradual arrival in Canaan, may have claimed that it was his idea to let them reside in this territory. Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. Ramesses III was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.[4]

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the Egypt's favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Set Maat her imenty Waset (now known as Deir el Medina), could not be provisioned.[5] Something in the air (but not necessarily Hekla 3) prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC. The result in Egypt was a substantial inflation in grain prices under the later reigns of Ramesses VI-VII whereas the prices for fowl and slaves remained constant.[6] The cooldown, hence, affected Ramesses III's final years and impaired his ability to provide a constant supply of grain rations to the workman of the Deir el-Medina community.

These difficult realities are completely ignored in Ramesses' official monuments, many of which seek to emulate those of his famous predecessor, Ramesses II, and which present an image of continuity and stability. He built important additions to the temples at Luxor and Karnak, and his funerary temple and administrative complex at Medinet-Habu is amongst the largest and best-preserved in Egypt; however, the uncertainty of Ramesses' times is apparent from the massive fortifications which were built to enclose the latter. No Egyptian temple in the heart of Egypt prior to Ramesses' reign had ever needed to be protected in such a manner.

Ramesses' two main names transliterate as wsr-m3‘t-r‘–mry-ỉmn r‘-ms-s–ḥḳ3-ỉwnw. They are normally realised as Usermaatre-meryamun Ramesse-hekaiunu, meaning "Powerful one of Ma'at and Ra, Beloved of Amun, Ra bore him, Ruler of Heliopolis".

[edit] Conspiracy against the king

Thanks to the discovery of papyrus trial transcripts (dated to Ramesses III), it is now known that there was a plot against his life as a result of a royal harem conspiracy during a celebration at Medinet Habu. The conspiracy was instigated by Tey, one of his two known wives (the other being Iset Ta-Hemdjert), over whose son would inherit the throne. Iset's son, Ramesses (the future Ramesses IV), was the eldest and the successor chosen by Ramesses III in preference to Tey's son Pentawere.

The trial documents[7] emphasize the extensive scale of the conspiracy to assassinate the king since many individuals were implicated in the plot.[8] Chief among them were Queen Tey and her son Pentawere, Ramesses' chief of the chamber, Pebekkamen, seven royal butlers (a respectable state office), two Treasury overseers, two Army standard bearers, two royal scribes and a herald. There is little doubt that all of the main conspirators were executed: some of the condemned were given the option of committing suicide (possibly by poison) rather than being put to death.[9] According to the surviving trials transcripts, 3 separate trials were started in total while 38 people were sentenced to death.[10] The tombs of Tey and her son Pentawere were robbed and their names erased to prevent them from enjoying an afterlife. The Egyptians did such a thorough job of this that the only references to them are the trial documents and what remains of their tombs.

Some of the accused harem women tried to seduce the members of the judiciary who tried them but were caught in the act. Judges who took part in the carousing were severely punished.[11]

Historian Susan Redford speculates that Pentawere, being a noble, was given the option to commit suicide by taking poison and so be spared the humiliating fate of some of the other conspirators who would have been burned alive with their ashes strewn in the streets. Such punishment served to make a strong example since it emphasized the gravity of their treason for ancient Egyptians who believed that one could only attain an afterlife if one's body was mummified and preserved — rather than being destroyed by fire. In other words, not only were the criminals killed in the physical world; they did not attain an afterlife. They would have no chance of living on into the next world, and thus suffered a complete personal annihilation. By committing suicide, Pentawere could avoid the harsher punishment of a second death. This could have permitted him to be mummified and move on to the afterlife.

It is not known if the assassination plot succeeded. Ramesses III died in his 32nd year before the summaries of the sentences were composed.[12] His body shows no obvious wounds.[11] But some measures would have left little or no visible traces on the body. Among the conspirators were practitioners of magic,[13] who might well have used poison. Some have put forth a hypothesis that a snakebite from a viper was the cause of the king's death but this proposal has not been proven. His mummy includes an amulet to protect Ramesses III in the afterlife from snakes. The servant in charge of his food and drink were also among the listed conspirators, but there were also other conspirators who were called the snake and the lord of snakes.

In one respect the conspirators certainly failed. The crown passed to the king's designated successor: Ramesses IV. Ramesses III may have been doubtful as to the latter's chances of succeeding him since, in the Great Harris Papyrus, he implored Amun to ensure his son's rights.[14]

[edit] Legacy

The Great Harris Papyrus or Papyrus Harris I, which was commissioned by his son and chosen successor Ramesses IV, chronicles this king's vast donations of land, gold statues and monumental construction to Egypt's various temples at Piramesse, Heliopolis, Memphis, Athribis, Hermopolis, This, Abydos, Coptos, El Kab and other cities in Nubia and Syria. It also records that the king dispatched a trading expedition to the Land of Punt and quarried the copper mines of Timna in southern Canaan. Papyrus Harris I records some of Ramesses III activities:

| “ | I sent my emissaries to the land of Atika, [ie: Timna] to the great copper mines which are there. Their ships carried them along and others went overland on their donkeys. It had not been heard of since the (time of any earlier) king. Their mines were found and (they) yielded copper which was loaded by tens of thousands into their ships, they being sent in their care to Egypt, and arriving safely." (P. Harris I, 78, 1-4)[15] | ” |

More notably, Ramesses began the reconstruction of the Temple of Khonsu at Karnak from the foundations of an earlier temple of Amenhotep III and completed the Temple of Medinet Habu (temple) around his Year 12.[16] He decorated the walls of his Medinet Habu temple with scenes of his Naval and Land battles against the Sea Peoples. This monument stands today as one of the best-preserved temples of the New Kingdom.[17]

The mummy of Ramesses III was discovered by antiquarians in 1886 and is regarded as the prototypical Egyptian Mummy in numerous Hollywood movies.[18] His tomb (KV11) is one of the largest in the Valley of the Kings.

[edit] Chronological dispute

Some scientists have tried to establish a chronological point for this pharaoh's reign at 1159 BC, based on a 1999 dating of the "Hekla 3 eruption" of the Hekla volcano at Iceland. Since contemporary records show that the king experienced difficulties provisioning his workmen at Deir el-Medina with supplies in his 29th Year, this dating of Hekla 3 might connect his 28th or 29th regnal year to circa 1159 BC.[19] A minor discrepancy of 1 year is possible since Egypt's granaries could have had reserves to cope with at least a single bad year of crop harvests following the onset of the disaster. This implies that the king's reign would have ended just 3 to 4 years later around 1156 or 1155 BC. A rival date of "2900 BP" or c.1000 BC has since been proposed by scientists based on a re-examination of the volcanic layer.[20] However, no Egyptologist dates Ramesses III's reign to as late as 1000 BC.

[edit] References

- ^ http://ib205.tripod.com/ramesses_3.html

- ^ E.F. Wente & C.C. Van Siclen, "A Chronology of the New Kingdom" in Studies in Honor of George R. Hughes, (SAOC 39) 1976, p.235, ISBN 0-918986-01-X

- ^ Hasel, Michael G. "Merenptah's Inscription and Reliefs and the Origin of Israel" in The Near East in the Southwest: Essays in Honor of William G. Dever" edited by Beth Albprt Hakhai The Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research Vol. 58 2003, quoting from Edgerton, W. F., and Wilson, John A. 1936 Historical Records of Ramses III, the Texts in Medinet Habu, Volumes I and II. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 12. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the Univer- sity of Chicago.

- ^ Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.271

- ^ William F. Edgerton, The Strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-Ninth Year, JNES 10, No. 3 (July 1951), pp. 137-145

- ^ Frank J. Yurco, p.456

- ^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §§423-456

- ^ Ramesses III: Egypt's last great pharaoh

- ^ James H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §§446-450

- ^ Joyce Tyldesley, Chronicle of the Queens of Egypt, Thames & Hudson October 2006, p.170

- ^ a b Cambridge Ancient History, Cambridge University Press 2000, p.247

- ^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, p.418

- ^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, pp.454-456

- ^ J. H. Breasted, Ancient Records of Egypt, Part Four, §246

- ^ A. J. Peden, The Reign of Ramesses IV, Aris & Phillips Ltd, 1994. p.32 Atika has long been equated with Timna, see here B. Rothenburg, Timna, Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines (1972), pp.201-203 where he also notes the probable port at Jezirat al-Faroun.

- ^ Jacobus Van Dijk, 'The Amarna Period and the later New Kingdom' in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, ed. Ian Shaw, Oxford University Press paperback, (2002) p.305

- ^ Van Dijk, p.305

- ^ Bob Brier, The Encyclopedia of Mummies, Checkmark Books, 1998., p.154

- ^ Frank J. Yurco, "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause" in Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente, ed: Emily Teeter & John Larson, (SAOC 58) 1999, pp.456-458

- ^ At first, scholars tried to redate the event to "3000 BP": TOWARDS A HOLOCENE TEPHROCHRONOLOGY FOR SWEDEN, Stefan WastegÅrd, XVI INQUA Congress, Paper No. 41-13, Saturday, July 26, 2003. Also: Late Holocene solifluction history reconstructed using tephrochronology, Martin P. Kirkbride & Andrew J. Dugmore, Geological Society, London, Special Publications; 2005; v. 242; p. 145-155.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Ramses III |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

En otros idiomas

- العربية

- Català

- Česky

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- English

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Suomi

- Français

- עברית

- Hrvatski

- Magyar

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Русский

- Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски

- Српски / Srpski

- Svenska

- Tiếng Việt

- 中 文

Category:Ramses III

From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

Contenido

Subcategories

This category has the following 9 subcategories, out of 9 total.

KM | PR | R cont.ST |

Media in category "Ramses III"

The following 42 files are in this category, out of 42 total.

![M17 [i] i](http://es.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_M17.png)

![X1 [t] t](http://es.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_X1.png)

![D21 [r] r](http://es.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_D21.png)

![F12 [wsr] wsr](http://es.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_F12.png)

![N35 [n] n](http://es.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png)

![N5 [ra] ra](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N5.png)

![F12 [wsr] wsr](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_F12.png)

![C10 [mAat] mAat](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_C10.png)

![M17 [i] i](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_M17.png)

![Y5 [mn] mn](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_Y5.png)

![N35 [n] n](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N35.png)

![F31 [ms] ms](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_F31.png)

![O34 [z] z](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_O34.png)

![S38 [HqA] HqA](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_S38.png)

![N29 [q] q](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_N29.png)

![O28 [iwn] iwn](http://en.wikipedia.org/w/extensions/wikihiero/img/hiero_O28.png)

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario