Ramesseum - Español

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

El Ramesseum es el nombre dado al templo funerario ordenado erigir por Ramsés II, y situado en la necrópolis de Tebas, en la ribera occidental del río Nilo, frente a la ciudad de Luxor, junto al pequeño templo dedicado a su madre Tuya.

El nombre fue acuñado por Jean-François Champollion, que visitó sus ruinas en 1829 y fue el primero en identificar los nombres y títulos de Ramsés en sus muros. Su nombre original era Casa del millón de años de Usermaatra Setepenra, que une la ciudad de Tebas con el reino de Amón.[1]

Ocupa una superficie de diez hectáreas.

Contenido |

Ramsés II [editar]

Ramsés fue un faraón de la Decimonovena Dinastía de Egipto. Gobernó durante 67 años, en el siglo XIII a. C., en el apogeo del poder y la gloria de Egipto. La duración fuera de lo común de su reinado, la abundancia del erario público y la vanidad personal del faraón, hizo de Ramsés un rey que dejó un recuerdo imborrable en el país.

Su herencia se puede comprobar en el legado arqueológico, en los muchos edificios que Ramsés construyó, amplió o usurpó en todo el territorio egipcio. El más espléndido de ellos, construido de acuerdo con las prácticas funerarias del Imperio Nuevo habría sido su templo conmemorativo: un lugar dedicado a la adoración del faraón, casi un dios en la tierra, donde su memoria se mantendría viva después de su paso por este mundo. Los registros existentes indican que se comenzó a trabajar en el proyecto poco después del comienzo de su reinado, y continuó durante veinte años.

Descripción [editar]

Tiene una estructura clásica: el templo funerario de Ramsés sigue los cánones de la arquitectura de templos del Imperio Nuevo, orientado de noroeste a sureste, con dos pilonosShalem, en la que algunos creen ver a Jerusalén. de 68 metros de anchura. En el primer pilono se registra su conquista, el octavo año de su reinado, de una ciudad llamada

En el primer patio se encontraban los dos colosos sedentes del faraón Ramsés II, de los que sólo quedan fragmentos de la base y del torso de 17 metros de altura.

El palacio real está la izquierda de este patio, y las estatuas del rey al fondo.[2]

Los restos del segundo patio incluyen la fachada interna del segundo pilono y una porción del pórtico de Osiris a la derecha.[2] En los muros están grabados los bajorrelieves del Poema de Pentaur que describen la batalla de Qadesh,[2] y un festival en honor a Min, dios de la fertilidad. Las dos estatuas del rey, una en granito rosado y la otra en granito negro, flanquean la puerta del templo.[2]

Treinta y nueve de las cuarenta y ocho columnas campaniformes con capiteles papiriformesoro en un fondo azul, que permanece bien conservado,[2] y los hijos e hijas de Ramsés aparecen en procesión en los muros de la izquierda. En el muro oriental están los bajorrelieves que narran el asalto a la fortaleza de Dapur. El santuario está compuesto por tres cuartos consecutivos, con ocho columnas, en uno de los cuales se guardaba la barca sagrada. Restos del primer cuarto, con el techo decorado con motivos astronómicos, y algunos restos del segundo cuarto son todo lo que se conserva.[2] todavía se mantienen en pie en la sala hipóstila, adornadas con escenas del rey ante varios dioses. El techo está pintado con estrellas de

Al norte y adyacente a la sala hipostila hay un templo más pequeño, dedicado a su madre, Tuya, donde se encontraba una estatua de la reina de 227 cm de altura, que fue llevada a Roma en tiempos de Calígula.[3]

El complejo estaba rodeado por varios almacenes, graneros, talleres, y otros edificios auxiliares, algunos construidos posteriormente, incluso en época romana.

Un templo dedicado a Seti I, del cual sólo quedan los cimientos, estaba a la derecha de la sala hipóstila. Todo el conjunto estaba rodeado por un muro de adobe que comenzaba en el pilono suroriental.

Se han encontrado papiros y ostraca fechados en el Tercer periodo intermedio, siglo XI a. C. al VIII que indican que el templo tenía también una escuela importante, y que fue un centro económico, cultural y religioso.

Ramsés edificó este templo sobre una tumba del Imperio Medio, en la que se han encontrado muchos objetos relativos al culto funerario.

Conservación [editar]

Desgraciadamente, la piedra caliza, semejante a la de los templos Abu Simbel, que se usó para el Templo del millón de años no era la más adecuada para construir en Tebas, debido a la humedad por su situación junto al Nilo, cuyas inundaciones anuales fueron minando sus cimientos. La negligencia y la llegada de nuevas religiones también le afectaron: fue convertido en iglesia cristiana.

Dejando a un lado la escalada de tamaño, por la que cada nuevo faraón se esforzaba en aventajar a sus predecesores en el volumen y tamaño de sus obras, el Ramesseum pertenece en parte al mismo tipo que el de Medinet Habu, de Ramsés III, o al templo perdido de Amenhotep III que estaba situado tras los Colosos de Memnón, apenas a un kilómetro de distancia.

Excavaciones y estudios [editar]

Los orígenes de la egiptología se pueden remontar a la llegada a Egipto de Napoleón Bonaparte en el verano de 1798. Evidentemente era la invasión de una potencia imperialista, pero influido por las ideas de la Ilustración, pero Napoleón llevó junto a sus tropas hombres de ciencia, que más tarde escribieron más de veinte tomos con la Descripción de Egipto.[4]

Entre ellos iban dos ingenieros, Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois y Édouard de Villiers du Terrage a quienes se asignó el estudio del Ramesseum, y lo identificaron como la Tumba de Osimandias o Palacio de Memnon, sobre el que Diodoro de Sicilia había escrito en el siglo I, llamando Osimandias al rey por una mala transcripción de su nombre: User-Maat-Ra (Ramsés II).

El siguiente visitante fue el italiano Giovanni Belzoni, un feriante de profesión e ingeniero por vocación, convertido en coleccionista y vendedor de antigüedades. En 1815 llegó a El Cairo, en donde entró en tratos con el cónsul británico Henry Salt que le encargó recoger y trasladar del Ramesseum a Inglaterra uno de los bustos colosales de granito del llamado joven Memnon –en realidad se trataba de un gran fragmento de una estatua de Ramsés II. Gracias a sus conocimientos de hidraúlica, Belzoni conseguía que la estatua de siete toneladas llegase a Londres en 1818. La expectación que levantó su llegada al museo fue grande, hasta el punto de que Percy Bysshe Shelley le dedicó su poema Ozymandias.[5] En 1829 Champollion visitó el lugar y tradujo sus jeroglíficos, con lo que se logró conocer la finalidad del edificio y la identidad de su constructor.

En 1858 se crea el Servicio de Antigüedades y desde 1967 el gobierno egipcio tiene un organismo creado por el egiptólogo Christiane Desroches Noblecourt, el Centro Franco-Egipcio para el estudio de los Templos de Karnak (CFEETK), que tiene la misión de conservar el conjunto arquitectónico de esta zona.

Notas [editar]

- ↑ Guy Lecuyot. «The Ramesseum (Egypt), recent Archaeological research». Archéologies d'Orient et d'Occident.

- ↑ a b c d e f Ania Skliar, Grosse kulturen der welt-Ägypten, 2005.

- ↑ Estatua de Tuya en el Museo Vaticano. Consultado el 27.07.07.

- ↑ Description de l'Égypte ou Recueil des observations et des recherches qui ont été faites en Égypte pendant l'expédition de l'armée française; Primera edición (23 tomos), L'Imprimerie Imperiale, 1809-1813.

- ↑ Ozymandias de Shelley Consultado el 27.07.07

Galería [editar]

Enlaces externos [editar]

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Ramesseum.Commons

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Ramesseum.Commons- Situación:

- Descripción y plano

- El Ramesseum

- Templos del Imperio Nuevo

Ramesseum - Inglés

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Ramesseum is the memorial temple (or mortuary temple) of Pharaoh Ramesses IIThebannecropolis in Upper Egypt, across the River Nile from the modern city of Luxor. The name – or at least its French form, Rhamesséion – was coined by Jean-François Champollion, who visited the ruins of the site in 1829 and first identified the hieroglyphs making up Ramesses's names and titles on the walls. It was originally called the House of millions of years of Usermaatra-setepenra that unites with Thebes-the-city in the domain of Amon.[1] ("Ramesses the Great", also spelled "Ramses" and "Rameses"). It is located in the

Most splendid of these, in accordance with New Kingdom Royal burial practices, would have been his memorial temple: a place of worship dedicated to pharaoh, god on earth, where his memory would have been kept alive after his passing from this world. Surviving records indicate that work on the project began shortly after the start of his reign and continued for 20 years.

The design of Ramesses's mortuary temple abides by the standard canons of New Kingdom temple architecture. Oriented northwest and southeast, the temple itself comprised two stone pylons (gateways, some 60 m wide), one after the other, each leading into a courtyard. Beyond the second courtyard, at the centre of the complex, was a covered 48-column hypostyle hall, surrounding the inner sanctuary.

An enormous pylon (gateways, some 60 m wide) stood before the first court, with the royal palace at the left and the gigantic statue of the king looming up at the back.[2]

As is customary, the pylons and outer walls were decorated with scenes commemorating pharaoh's military victories and leaving due record of his dedication to, and kinship with, the gods. In Ramesses's case, much importance is placed on the Battle of Kadesh (ca. 1285 BC); more intriguingly, however, one block atop the first pylon records his pillaging, in the eighth year of his reign, a city called "Shalem", which may or may not have been Jerusalem.

The scenes of the great pharaoh and his army triumphing over the Hittite forces fleeing before Kadesh, represented in line with the canons of the "epic poem of Pentaur", can still be made out of the pylon.[2]

Only fragments of the base and torso remain of the syenite statue of the enthroned pharaoh, 62 feet (19 metres) high and weighing more than 1000 tons. This was alleged to have been transported 170 miles over land. This is the largest remaining colossal statue (except statues done in situ) in the world. However fragments of 4 granite Colossi of Ramses were found in Tanis (northern Egypt). Estimated height is 69 to 92 feet (21 to 28 meters). Like four of the six colossi of Amenhotep III (Colossi of Memnon) there are no longer complete remains so it is based partly on unconfirmed estimates. [3] [4]

Remains of the second court include part of the internal façade of the pylon and a portion of the Osiride portico on the right.[2] Scenes of war and the rout the Hittites at Kadesh are repeated on the walls.[2] In the upper registers, feast and honour of the phallic god Min, god of fertility.[2] On the opposite side of the court the few Osiride pillars and columns still left can furnish an idea of the original grandeur.[2] Scattered remains of the two statues of the seated king can also be seen, one in pink granite and the other in black granite, which once flanked the entrance to the temple. The head of one of these has been removed to the British Museum.[5][2] Thirty-nine out of the forty-eight columns in the great hypostyle hall (m 41x 31) still stand in the central rows. They are decorated with the usual scenes of the king before various gods. Part of the ceiling decorated with gold stars on a blue ground has also been preserved.[2] The sons and daughters of Ramesses appear in the procession on the few walls left. The sanctuary was composed of three consecutive rooms, with eight columns and the tetrastyle cell.[2] Part of the first room, with the ceiling decorated with astral scenes, and few remains of the second room are all that is left.[2]

Adjacent to the north of the hypostyle hall was a smaller temple; this was dedicated to Ramesses's mother, Tuya, and his beloved chief wife, Nefertari. To the south of the first courtyard stood the temple palace. The complex was surrounded by various storerooms, granaries, workshops, and other ancillary buildings, some built as late as Roman times.

A temple of Seti I, of which nothing is now left but the foundations, once stood to the right of the hypostyle hall. It consisted of a peristyle court with two chapel shrines. The entire complex was enclosed in mud brick walls which started at the gigantic southeast pylon.

A cache of papyri and ostraca dating back to the third intermediate period (11th to 8th centuries BC) indicates that the temple was also the site of an important scribal school.

The site was in use before Ramesses had the first stone put in place: beneath the hypostyle hall, modern archaeologists have found a shaft tomb from the Middle Kingdom, yielding a rich hoard of religious and funerary artifacts.

Contents |

[edit] Remains

Unlike the massive stone temples that Ramesses ordered carved from the face of the NubianAbu Simbel, the inexorable passage of three millennia was not kind to his "temple of a million years" at Thebes. This was mostly due to its location on the very edge of the Nile floodplain, with the annual inundation gradually undermining the foundations of this temple, and its neighbours. Neglect and the arrival of new faiths also took their toll: for example, in the early years of the Common Era, the temple was put into service as a Christianchurch. mountains at

This is all standard fare for a temple of its kind built at the time it was. Leaving aside the escalation of scale – whereby each successive New Kingdom pharaoh strove to outdo his predecessors in volume and scope – the Ramesseum is largely cast in the same mould as Ramesses III's Medinet Habu or the ruined temple of Amenhotep III that stood behind the "Colossi of Memnon" a kilometre or so away. Instead, the significance that the Ramesseum enjoys today owes more to the time and manner of its rediscovery by Europeans.

[edit] Excavation and Studies

The origins of modern Egyptology can be traced to the arrival in Egypt of Napoleon BonaparteEnlightenment ideas: alongside Napoleon's troops went men of science, the same whose toil under the desert sun would later yield the seminal 23-volume Description de l'Égypte. Two French engineers, Jean-Baptiste Prosper Jollois and Édouard de Villiers du Terrage, were assigned to study the Ramesseum site, and it was with much fanfare that they identified it with the "Tomb of Ozymandias" or "Palace of Memnon" of which Diodorus of Sicily had written in the 1st century BC. in the summer of 1798. While undeniably an invasion by an alien imperialist power, this was nonetheless an invasion of its times, informed by

The next visitor of note was Giovanni Belzoni, a showman and engineer of Italian origin and, latterly, an archaeologist and antiques dealer. Belzoni's travels took him in 1815 to Cairo, where he sold Mehemet Ali a hydraulic engine of his own invention. There he met British Consul General Henry Salt, who hired his services to collect from the temple in Thebes the so-called 'Younger Memnon', one of two colossal granite heads depicting Ramesses II, and transport it to England. Thanks to Belzoni's hydraulics and his skill as an engineer (Napoleon's men had failed in the same endeavour a decade or so earlier), the 7-ton stone head arrived in London in 1818, where it was dubbed "The Younger Memnon" and, some years later, given pride of place in the British Museum.

It was against the backdrop of intense excitement surrounding the statue's arrival, and having heard wondrous tales of other, less transportable treasures still in the desert, that the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley penned his sonnet "Ozymandias". In particular, one massive fallen statue at the Ramesseum is now inextricably linked with Shelley, because of the cartouche on its shoulder bearing Ramesses's throne name, User-maat-re Setep-en-re, the first part of which Diodorus transliterated into Greek as "Ozymandias". While Shelley's "vast and trunkless legs of stone" owe more to poetic license than to archaeology, the "half sunk... shattered visage" lying on the sand is an accurate description of part of the wrecked statue. The hands, and the feet, lie nearby. Were it still standing, the Ozymandias colossus would tower 18 metres above the ground, rivalling the Colossi of Memnon and the statues of Ramesses carved into the mountain at Abu Simbel.

[edit] Pictures from the Ramesseum

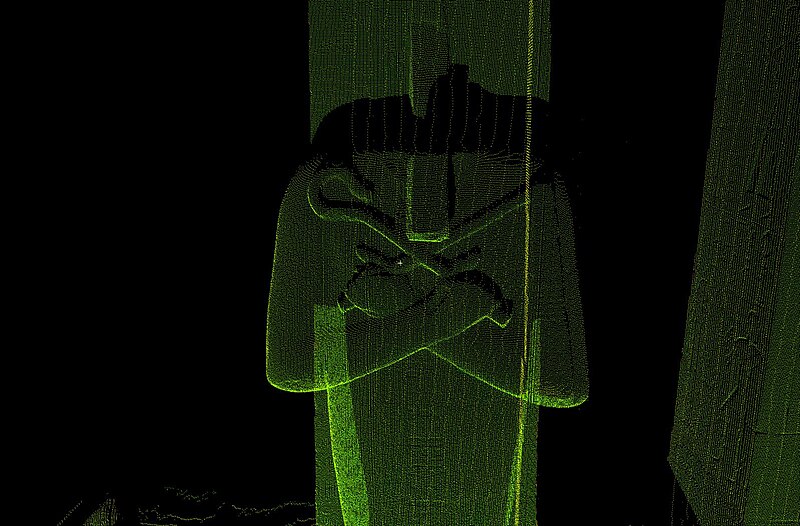

| Photo-textured laser scan elevation of Ramesseum First Pylon, Thebes. | Contour Image of Thebes' Ramesseum Hypostyle Hall, Egypt, cut from a Laser Scan. |

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Guy Lecuyot. "THE RAMESSEUM (EGYPT), RECENT ARCHAEOLOGICAL RESEARCH". Archéologies d'Orient et d'Occident. http://web.archive.org/web/20070606144645/http://www.archeo.ens.fr/8546-5Gren/clrweb/7dguylecuyot/GLRamesseumWeb.html. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Ania Skliar, Grosse kulturen der welt-Ägypten, 2005

- ^ "The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World" edited by Chris scarre 1999

- ^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/03/080331-egypt-statue.html

- ^ http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/search_object_details.aspx?objectid=117633&partid=1&searchText=younger+memnon&fromADBC=ad&toADBC=ad&numpages=10&orig=%2fresearch%2fsearch_the_collection_database.aspx¤tPage=1

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Ramesseum |

- Association pour la sauvegarde du Ramesséum (particularly the "virtual restoration")

- Plan of the Ramesseum site (University College London)

- Ramesseum Digital Media Archive (photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from an Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities/CyArk research partnership

- The Younger Memnon (British Museum)

- Ozymandias (Shelley)

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| |||||||

Coordinates: 25°43′40″N 32°36′38″E / 25.72778°N 32.61056°E

Categories: 13th-century BC architecture | Theban NecropolisEn otros idiomas

- العربية

- Català

- Česky

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- English

- Euskara

- Français

- עברית

- Magyar

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Polski

- Português

- Русский

- Svenska

Temples of Millions of Years Colloquium

http://www.egyptologyforum.org/bbs/ConfTMY.pdf

Iman R. Abdulfattah

Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA)

3 el-Adel Abu Bakr Street

Zamalek, Cairo, Egypt

http://www.sca.gov.eg/

Ramesseum - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Casa del millón de años - Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre