Dinastía IV de Egipto

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

La Cuarta Dinastía forma parte del Imperio Antiguo de Egipto. Se inicia cerca de 2630 a. C.Seneferu y termina ca. 2500 a. C. con el de Shepseskaf (o tal vez con Dyedefptah, citado por Manetón). Estos faraones mantuvieron su capital en Menfis, como los de la dinastía III. No se conoce bien cómo finalizó esta dinastía; el único indicio es que varios dirigentes y altos funcionarios de la cuarta dinastía están documentados permaneciendo con el mismo cargo durante la siguiente dinastía V bajo el reinado de Userkaf. con el reinado de

Contenido |

La dinastía IV en los textos antiguos [editar]

- La Lista Real de Abidos y la Lista Real de Saqqara nos muestran los faraones más importantes de esta dinastía.

- El Canon Real de Turín, que registra algunos nombres de los reyes de esta dinastía, cita dos nombres perdidos, que el escriba indicó con la palabra egipcia usf, "perdidos".

- Sexto Julio Africano informa que Manetón dio los nombres Bijeris y Tamftis en esas posiciones, mientras que Eusebio de Cesarea no los menciona. Algunas autoridades (tal como K. S. B. Ryholt) sugieren que Africano da una posible versión egipcia de estos nombres en su lista; otros lo descartan totalmente.

- Los primeros documentos conocidos del contacto de Egipto con sus vecinos son escritos durante esta dinastía. La Piedra de Palermo registra la llegada de cuarenta barcos cargados con madera procedentes de una tierra extranjera innominada durante el reinado de Seneferu.

- Los nombres de Jufu y Dyedefra se grabaron en las canteras de gneis el desierto occidental, 65 km al noroeste de Abu Simbel; objetos fechados en los reinados de Jufu, Jafra, y Menkaura se ha descubierto en Biblos y del reinado de Jafra aun más lejos, en Ebla, como evidencia de obsequios diplomáticos o tratos comerciales.

Faraones de la Dinastía IV [editar]

| Nombre | Nombre helenizado | Comentarios | Años de reinado |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seneferu | Emprendió expediciones bélicas contra Nubia y Libia | 24 | |

| Jufu | Keops | Heródoto le atribuye la Gran Pirámide de Giza, con la colaboración de su hija | 23 |

| Dyedefra | Se le atribuye la pirámide, totalmente en ruinas, de Abu Roash, situada unos ocho km al norte de Giza | 8 | |

| Jafra | Kefrén | Herodoto le atribuye la segunda pirámide de Giza, también se le atribye la Gran Esfinge de Giza. | (25) |

| Dyedefhor | Posiblemente solo gobernó como corregente | - | |

| Baefra | Gobernante efímero | 2 (?) | |

| Menkaura | Micerino | Se le atribuye la tercera pirámide de Giza. Su sarcófago reposa frente a las costas de Cartagena (España) | 28 |

| Shepseskaf | Se hizo construir, como edificio funerario, una enorme mastaba al sur de Saqqara | 4 | |

| Dyedefptah | Incluido por algunos egiptólogos siguiendo a Manetón (Tamftis) | (?) |

- Años de reinado según el Canon Real de Turín

Referencias en las Listas Reales y otros textos [editar]

| Nombre | Nombre de Horus | Lista Real de Abidos | Lista Real de Saqqara | Canon Real de Turín | Manetón | Heródoto | Periodo de reinado (± 100 años) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seneferu | Nebmaat | Seneferu | Seneferu | Senefer (24) | Soris | 2630 a. C. - 2605 a. C. | |

| Jufu | Medyedu | Jufu | Jufu | ilegible (23) | Sufis I | Keops | 2605 a. C. - 2580 a. C. |

| Dyedefra | Jeper | Dyedefra | Dyedefra | ilegibile (8) | Ratoises | 2580 a. C. - 2570 a. C. | |

| Jafra | Userib | Jafra | Jafura | Ja... | Sufis II | Kefrén | 2570 a. C. - 2550 a. C. |

| Dyedefhor | c. 2550 a. C. | ||||||

| Baefra | ilegibile (2) ? | Bikeris | c. 2550 a. C. | ||||

| Menkaura | Kayet | Menkaura | Menkaura | ilegibile (18 o 28) | Menkeres | Micerino | 2535 a. C. - 2515 a. C. |

| Shepseskaf | Shepsejet | Shepseskaf | perdido | ilegibile (4) | Seberkeres | c. 2510 a. C. | |

| Dyedefptah | perdido | ilegibile | Tamftis | c. 2510 a. C. |

- Para Manetón, según Julio Africano en la versión del monje Sincelo, la dinastía IV comprendió ocho reyes de Menfis, en este orden:

Soris (29), Sufis (63), Sufis (66), Menkeres (63), Ratoises (25), Bikeris (22), Seberkeres (7) y Tamftis (9) (años de reinado entre paréntesis)

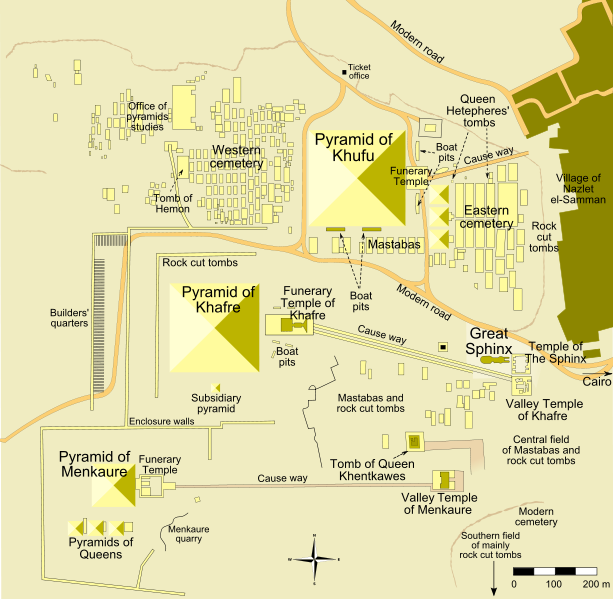

Edificaciones atribuidas a la dinastía IV [editar]

- Esta dinastía incluye algunos de los faraones más populares del antiguo Egipto, célebres por habérsele adjudicado construir las mayores pirámides, quizás lo más distintivo de Egipto. Casi todos los reyes de esta dinastía ordenaron erigir por lo menos una pirámide para servirles como cenotafio o tumba.

- Seneferu, el fundador de la dinastía, es conocido por haber encargado construir tres pirámides, y algunos creen que era responsable de una cuarta. Aunque Jufu, su sucesor y el hijo de Hetepheres I, erigiera la pirámide más grande en Egipto, Seneferu ordenó mover más piedras y ladrillos que cualquier otro faraón.

- Jufu (Keops en griego), su hijo Jafra (Kefrén en griego), y su nieto Menkaura (MicerinoImperio Antiguo mostró en este momento este nivel de sofisticación. Aunque se creyó alguna vez que fueron esclavos los que construyeron estos monumentos, el estudio de las pirámides y sus alrededores ha revelado que fueron construidas por grupos de campesinos de todo Egipto, que supuestamente trabajaron mientras la inundación anual de Nilo cubría sus campos. en griego) lograron larga fama con la construcción de sus pirámides. Para organizar y alimentar a los trabajadores necesarios para erigir estas pirámides se requería un gobierno centralizado con amplios poderes, y los egiptólogos creen que el

- Mientras las pirámides sugieren que en Egipto se gozó de incomparable prosperidad durante la cuarta dinastía, estas permanecieron como un recordatorio para los egipcios de los trabajos forzados a que los sometieron, y estos reyes, Jufu en particular, fueron recordados como tiranos: primero en el Papiro Westcar, y milenios después en las leyendas recogidas por Heródoto.

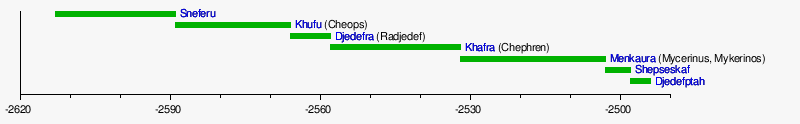

Cronología de la dinastía IV [editar]

Cronología estimada por los siguientes egiptólogos:

|

|

Cronograma [editar]

Otras hipótesis [editar]

- Herodoto escribió que Keops tuvo por hermano a Kefrén, y por hijo a Micerino.

Referencias [editar]

- Referencias digitales

- (en inglés) http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk//Welcome.html

- (en inglés) http://www.ancient-egypt.org/index.html

- (en alemán) http://www.eglyphica.de/egpharaonen

Enlaces externos [editar]

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre la dinastía IV de Egipto.

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre la dinastía IV de Egipto.- Genealogía, Reyes y Reinos: Dinastía IV de Egipto

| Dinastía precedente | Imperio Antiguo de Egipto | Dinastía siguiente |

|---|---|---|

| Dinastía III | Dinastía IV | Dinastía V |

Fourth dynasty of Egypt

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Fourth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, also written as Dynasty 4 and Dynasty IV, is characterized as a "golden age" of the Old Kingdom. The fourth dynasty lasted from from ca. 2575 to 2467 BCE. It was a time of peace and prosperity as well as one during which trade with other countries is documented.

The third, fourth, fifth, and sixth dynasties are often combined under the group title, the Old Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, which often is described as the age of the pyramids. The capital at that time was Memphis.

Contents |

[edit] Fourth-Dynasty Kings

The Fourth Dynasty heralded the height of the pyramid-building age. The relative peace of the Third Dynasty allowed the Fourth Dynasty the leisure to explore more artistic and cultural pursuits. Sneferu’s building experiments led to the evolution from the mastabaGiza plateau. No period before or after the Egypt’s history equaled the Fourth Dynasty’s architectural accomplishments. [1] All of the rulers of this dynasty commissioned at least one pyramid to serve as a tomb or cenotaph. styled step pyramids to the smooth sided “true” pyramids, such as those on the

[edit] Sneferu

Sneferu, the first king of the Fourth Dynasty, is given the credit of completing the first true pyramid. He called it the Red Pyramid, it was created after he built and abandoned the Bent Pyramid and probably after he finished the Meidum Pyramid. He also constructed a number of smaller step pyramids, making him the most prolific pyramid builder of the era.[2] It is said that Sneferu had more stone and brick moved than any other pharaoh.

Sneferu’s first wife was Hetepheres I, his half-sister and mother of his sons Khnum and Khufu. His second wife also had two sons, Netjerape and Nefermaat. Besides these four children, he is also known to have at least five more children by other wives or consorts.[3]

A well-liked ruler, Sneferu bolstered the power of the ruling family line by giving official titles and positions to relatives. He maintained control over the nobility by keeping a tight rein on lands and estates. He conducted military excursions into Sinai, Nubia, Libya, and began trade arrangements with Lebanon for the acquisition of cedar.[4]

Surviving from this era are the earliest-known records of Egyptian contact with her neighbors. They are recorded on the Palermo stone. Information carved on the stone predates and antedates this dynasty. Although some portions of the stone are lost, one remaining portion contains notations about the arrival of forty ships laden with timber from an unnamed foreign land purchased during the reign of Sneferu.

[edit] Khufu, Djedefra, Khafra, and Menkaura

The names of Khufu and Djedefra were inscribed in gneiss quarries in the Western Desert 65 km. to the northwest of Abu Simbel; objects dated to the reigns of Khufu, Khafra, and Menkaura have been uncovered at Byblos. Objects dating to the reign of Khafra have been found even farther away, at Ebla, where there is evidence of diplomatic gifts or trade also.

Khufu is the ruler who is known in Greek as Χέοψ - Cheops. His son is Khafra (Greek Χεφρήν - Chephren) and his grandson is Menkaura (Greek Μυκερίνος - Mycerinus). All of these rulers achieved lasting fame in the construction of their pyramids at Giza.

Organizing and feeding the workforce needed to create these pyramids required a centralized government with extensive powers, and Egyptologists believe that at this time the Old Kingdom demonstrated this level of sophistication and the long period of prosperity required to accomplish such projects. In fact, recent excavations outside the Wall of the Crow by Dr. Mark Lehner have uncovered a large city which seems to have housed, fed, and supplied the pyramid workers.

Although it was once believed that slaves built these monuments—a bias based on the biblical Exodus story—study of the tombs of the workers who oversaw construction on the pyramids, has shown that they were built by a corvée of peasants drawn from across Egypt. Apparently, they worked during idle periods, while the annual Nile flood covered their fields, along with a very large crew of specialists including stone cutters, painters, mathematicians, and priests. Some records indicate that each household was responsible for providing a worker for civic projects and the wealthy could hire others to take their places. Civic duties were not necessarily building projects, there were duties for the temples, libraries, and festivals as well, and both men and women filled some of the positions.

These pyramids suggest that Egypt enjoyed unparalleled prosperity during the fourth dynasty. The later bias of Herodotus (Histories, 2.124-133) has helped instill the idea that the pyramids survived as a reminder to the inhabitants of the forced labor that created them, however, although there was a tradition of the negative memory of Khufu presented in Papyrus Westcar, these kings were not tyrannized. In fact, the very same Papyrus Westcar presents Snefru in a very benevolent light—even though he moved more stone to construct his pyramids than Khufu. This demonstrates that these pharaohs may have been remembered for their own individual reigns and personalities, rather than the sheer size of the monuments they built-monuments which in all probability, were built by a "willing" public.

[edit] Khentykawes I

Perhaps most intriguing is the status of Khentykawes I, whose tomb was built along the Menkaura causeway.

Khentykawes was the wife and royal queen of Menkaura and may have been the mother of Shepseskaf, first king of the fifth dynasty. She also may have ruled as pharaoh.

Her tomb is a large mastaba tomb, with another off-center mastaba placed above it. The second mastaba could not be centered because of the free, unsupported, space in the rooms below, in her primary mastaba.

On a granite doorway leading into her tomb, Khentykawes is given titles which may be read either as mother of two kings of upper and lower Egypt or, as mother of the king of upper and lower Egypt and, king of upper and lower Egypt.

Furthermore, her depiction on this doorway also gives the her the full trappings of royalty, including the false beard of the pharaoh. This depiction and the title given have led some Egyptologists to suggest that she reigned as pharaoh near the end of the fourth dynasty.

Her tomb was finished by her son, Shepseskaf, in the characteristic niche architecture for which he is known. However, the niches were later filled in with a smooth casing of limestone.

[edit] Shepseskaf and Djedefptah

The next recorded pharaoh is Shepseskaf, son to Khentykawes I and Menkaura. His reign was short, but he completed the projects of his father and mother and established an architectural style of his own.

Djedefptah is a shadowy figure ascribed a reign of varying years, whose existence is questionable. Shepseskaf is usually considered to be the last pharaoh of the fourth dynasty. The ancient Egyptian historian, Manetho, however, lists a Tamphthis (which may be a corrupted form of Ptah-djedef) in this position, and the Turin Royal Canon, another resource about rulers, has an unnamed pharaoh listed who ruled for about two years after Shepseskaf. This ruler may be Djedefptah.

To date, it is unclear how this dynasty came to an end. Our only clue is that a number of fourth dynasty administrators are attested as remaining in office in the fifth dynasty under Userkaf.

[edit] Fourth Dynasty timeline

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ Egypt: Land and Lives of the Pharaohs Revealed, (2005), pg.80 -90, Global Book Publishing: Australia

- ^ Egypt: Land and Lives of the Pharaohs Revealed, (2005), pg.80 -90, Global Book Publishing: Australia

- ^ Egypt: Land and Lives of the Pharaohs Revealed, (2005), pg.80 -90, Global Book Publishing: Australia

- ^ Egypt: Land and Lives of the Pharaohs Revealed, (2005), pg.80 -90, Global Book Publishing: Australia

En otros idiomas

- العربية

- Български

- Brezhoneg

- Català

- Česky

- English

- Euskara

- Suomi

- Français

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Íslenska

- Italiano

- 日本語

- 한국어

- Nederlands

- Occitan

- Polski

- Português

- Română

- Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски

- Српски / Srpski

- Svenska

- Türkçe

- Українська

- 中文

| | Fotos de |

Egipto

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario