Book of the Dead

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series of articles on |

|---|

| Main Beliefs |

| Paganism · Pantheism · Polytheism Soul · Duat Mythology · Numerology |

| Practises |

| Offering formula · Funerals · Heka |

| Deities |

| Amun · Amunet · Anubis · Anuket Apep · Apis · Aten · Atum Bast · Bat · Bes · Chensit · Chenti-cheti Four sons of Horus Geb · Hapy · Hathor · Heget Horus · Isis · Khepry · Khnum Khonsu · Kuk · Maahes · Ma'at Mafdet · Menhit · Meretseger Meskhenet · Monthu · Min · Mnevis Mut · Naunet · Neith · Nekhbet Nephthys · Nut · Osiris · Pakhet Ptah · Ra · Ra-Horakhty · Reshep Satis · Sekhmet · Seker · Selket Sobek · Set · Seshat · Shu Taweret · Tefnut · Thoth Wadjet · Wadj-wer · Wepwawet · Wosret |

| Texts |

| Amduat · Books of Breathing Book of Caverns · Book of the Dead Book of the Earth · Book of Gates Book of the Netherworld |

| Other |

| Atenism · Curse of the Pharaohs |

| |

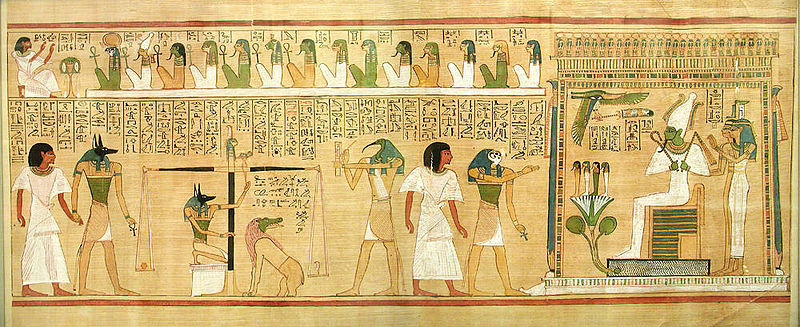

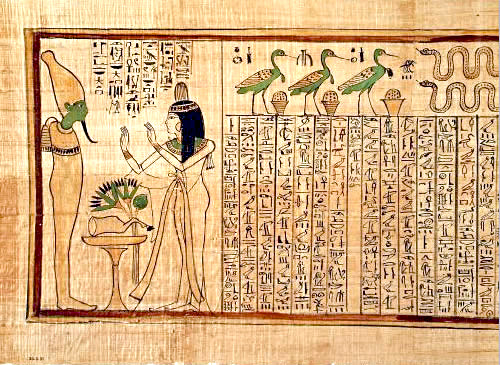

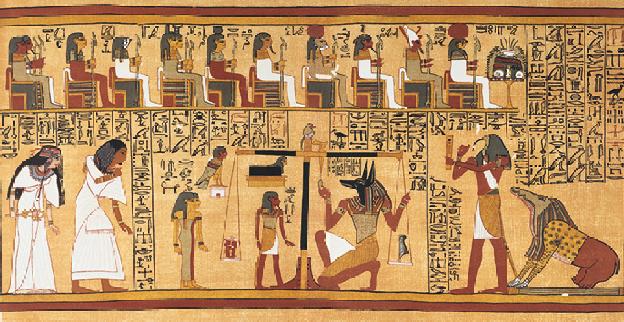

'The Book of the Dead' is the common name for the ancient Egyptian funerary text known as 'The Book of Coming '[or 'Going']' Forth By Day'. The book of the dead was a description of the ancient Egyptian conception of the afterlife and a collection of hymns, spells, and instructions to allow the deceased to pass through obstacles in the afterlife. The book of the dead was most commonly written on a papyrus scroll and placed in the coffin or burial chamber of the deceased.[1]

The name "Book of the Dead" was the invention of the German Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius, who published a selection of the texts in 1842. When it was first discovered, the book of the dead was thought to be an ancient Egyptian Bible. But unlike the Bible, The Book of the Dead does not set forth religious tenets and was not considered by the ancient Egyptians to be the product of divine revelation, which allowed the content of the book of the dead to change over time. The Book of the Dead was thus the product of a long process of evolution from the Pyramid texts of the Old Kingdom to the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom. About one-third of the chapters in The Book of the Dead are derived from the Coffin Texts.[2] The Book of the Dead itself was adapted to The Book of Breathings in the Late Period, but remained popular in its own right until the Roman period.

[edit] Versions

Although during the New Kingdom the book of the dead was not organized or standardized in any meaningful way, versions dating to this period are known as the 'Theban Recension'. In the Third Intermediate Period leading up to the Saite period, the book of the dead became increasingly standardized and organized, and books of this period are known as the 'Saite Recension'.

[edit] Saite recension

Early versions of the book of the dead were not standardized and were not organized by thematic content; however, this changed by the Saite period :

- Chapters 1-16 The deceased enters the tomb, descends to the underworld, and the body regains its powers of movement and speech.

- Chapters 17-63 Explanation of the mythic origin of the gods and places, the deceased are made to live again so that they may arise, reborn, with the morning sun.

- Chapters 64-129 The deceased travels across the sky in the sun ark as one of the blessed dead. In the evening, the deceased travels to the underworld to appear before Osiris.

- Chapters 130-189 Having been vindicated, the deceased assumes power in the universe as one of the gods. This section also includes assorted chapters on protective amulets, provision of food, and important places.[2] There are 192 unique chapters known, and no single papyrus contains all known chapters. Depending on the translation the verses are divided into Spell numbers as opposed to Chapter numbers.

[edit] Production

Books were often prefabricated in funerary workshops, with spaces being left for the name of the deceased to be written in later. They are often the work of several different scribes and artists whose work was literally pasted together. The cost of a typical book might be equivalent to half a year's salary of a laborer, so the purchase would be planned well in advance of the person's death. The blank papyrus used for the scroll often constituted the major cost of the work, so papyrus was often reused.[2]

Images, or vignettes to illustrate the text, were considered mandatory. The images were so important that often the text is truncated to fit the space available under the image. Whereas the quality of the miniatures is usually done at a high level, the quality of the text is often very bad. Scribes often misspelled or omitted words and inserted the wrong text under the images.

[edit] Further reading

- Thomas George Allen, The Egyptian Book of the Dead: Documents in the Oriental Institute Museum at the University of Chicago, Thomas George Allen, (University of Chicago Press, Chicago), c 1960.

- Thomas George Allen, The Book of the Dead or Going Forth by Day. Ideas of the Ancient Egyptians Concerning the Hereafter as Expressed in Their Own Terms, Thomas George Allen, (SAOC vol. 37; University of Chicago Press, Chicago), c 1974.

- E. A. Wallis Budge, The Egyptian Book of the Dead,(The Papyrus of Ani), Egyptian Text, Transliteration, and Translation, E.A.Wallis Budge, (Dover (Note: 240 pages of running hieroglyphic text. NB: Budge's translations and transliterations are extremely outdated and are not generally cited by modern Egyptologists)

- Raymond O. Faulkner, The Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead, translated by Raymond Faulkner, edited by Carol Andrews (University of Texas Press, Austin), c 1972.

- Raymond O. Faulkner, The Egyptian Book of the Dead, The Book of Going forth by Day. The First Authentic Presentation of the Complete Papyrus of Ani translated by Raymond Faulkner, edited by Eva von Dassow, with contributions by Carol Andrews and Ogden Goelet (Chronicle Books, San Francisco), c 1994.

- Gunther Lapp, The Papyrus of Nu (Catalogue of Books of the Dead in the British Museum), by Gunther Lapp, (British Museum Press, London), c 1997.

- Andrzej Niwinski, Studies on the Illustrated Theban Funerary Papyri of the 11th and 10th Centuries B.C., by Andrzej Niwinski, (OBO vol. 86; Universitätsverlag, Freiburg), c 1989.

[edit] References

- ^ "Feature story: The Book of the Dead" by Caroline Seawright

- ^ a b c Goelet, Ogden (1998). A Commentary on the Corpus of Literature and Tradition which constitutes the Book of Going Forth By Day. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 139-170.

[edit] External links

- Egyptian Book of the Dead

- Budge, E. A. Wallis, "Book of the Dead, The Papyrus of Ani".

- Online Readable Text, with several images and reproductions of Egyptian papyri

| |||||||

Libro de los Muertos

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

El Libro de los Muertos, o Peri Em Heru "Libro para salir al día", es un texto funerario compuesto por un conjunto de fórmulas mágicas o sortilegios, rau, que ayudaban al difunto, en su estancia en la Duat, a superar el juicio de Osiris, y viajar al Aaru, según la Mitología egipcia.

Origen y formación [editar]

La redacción del Libro de los Muertos se data durante el Imperio Nuevo, aunque para encontrar sus orígenes hay que remontarse a los Textos de las Pirámides del Imperio Antiguo que evolucionó posteriormente en los Textos de los Sarcófagos del Imperio Medio. Estas sucesivas transformaciones conllevan que esta colección heterogénea de fórmulas contenga textos funerarios de todas las épocas de la historia de Egipto. Destacan tres versiones diferentes del Libro de los Muertos, que se fueron sucediendo a través de la historia:

- La versión heliopolitana, redactada por los sacerdotes de Heliópolis para los faraones, se encuentra en algunos sarcófagos, estelas, papiros y tumbas de las dinastías XI, XII y XIII, aunque la esencia proviene de escritos primitivos. Netamente solar, promueve la teología del dios Ra.

- La versión tebana, escrita en jeroglíficos (y luego en hierático) sobre papiros, esta dividida en capítulos sin un orden determinado, aunque la gran mayoría tienen un título y una viñeta. Usada durante las dinastías XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX y XXI ya no solo por los faraones sino también por ciudadanos particulares.

- La versión saita dio lugar a su máxima expresión en la Dinastía XXVI de Egipto, en donde se fijaron el orden de los capítulos, que van a permanecer invariables hasta el final del período Ptolemáico.

Dyedefhor, que gozó de gran fama como sabio y adivino, es considerado el autor de la plegaria del Libro de los Muertos por la tradición.

Origen del título [editar]

El título "Libro de los Muertos" se debe a su primer editor y traductor, el egiptólogo alemán Karl Richard Lepsius, quien lo publicó en 1842 como Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter, aunque se dice también que el título procede del nombre que los profanadores de las tumbas dieron a los papiros con inscripciones que hallaron junto a las momias: Kitab al-Mayitun, en árabe, que significa "Libro del difunto". Los antiguos egipcios lo conocían como "Libro para salir al día".

Estructura [editar]

Por ahora se conocen un total de 192 capítulos, pero su extensión es muy desigual y no existe un solo papiro que los comprenda a todos. La extensión de los papiros variaba según el poder adquisitivo de cada difunto, y una vez que se fue popularizando, las versiones más económicas eran realizadas 'en serie' por los templos y luego rellenadas con el nombre del comprador. La sucesión de fórmulas, sin orden alguno y que llegan a variar de unos ejemplares a otros tienen, sin embargo, una lógica interna. Según el egiptólogo francés Paul Barguet, el Libro de los Muertos puede dividirse del modo siguiente:

- Capítulos 1-16: "Salir al día" (oración); marcha hacia la necrópolis, himnos al Sol y a Osiris.

- Capítulos 17-63: "Salir al día" (regeneración); triunfo y alegría; impotencia de los enemigos; poder sobre los elementos.

- Capítulos 64-129: "Salir al día" (transfiguración); poder manifestarse bajo diversas formas, utilizar la barca solar y conocer algunos misterios. Regreso a la tumba; juicio ante el tribunal de Osiris.

- Capítulos 130-162: Textos de glorificación del muerto, que se deben leer a lo largo del año, en determinados días festivos, para el culto funerario; servicio de las ofrendas. preservación de la momia por los amuletos.

- Capítulos 163-190: es un complemento de todo lo anterior, con fórmulas en donde se alaba a Osiris.

Capítulo 125 [editar]

Quizás el capítulo más famoso e importante del Libro de los Muertos sea el titulado "Fórmula para entrar en la sala de las dos Maat", en el cual el difunto se presenta ante el tribunal de Osiris al objeto de que se pese su corazón (conciencia y moralidad) y superada la prueba pueda continuar su camino en el mundo de los muertos, la Duat, hasta alcanzar los fértiles campos de Aaru.

Este capítulo, de notoria complejidad y extensión, contiene las llamadas "Confesiones negativas", declaraciones de inocencia que el difunto realizaba ante los dioses del tribunal a fin de justificar sus acciones personales, lo que pone de manifiesto la gran importancia moral que este capítulo significaba para los antiguos egipcios.

Papiros destacados [editar]

Por su extensión [editar]

- Papiro de Ani: es la versión más conocida y más completa del Libro de los Muertos, destacando su longitud (23,6 metros). Este papiro, realizado para el escriba real Ani (dinastía XIX), actualmente se encuentra en el Museo Británico, registrado bajo el nº 10.470. Fue traducido por Ernest Wallis Budge, y publicado en 1895.

- Papiro de Aufanj: actualmente en el Museo Egipcio de Turín, tiene una longitud de 19 metros y 165 capítulos.

Por su antigüedad [editar]

- Papiro de Iuya: se encuentra en el Museo Egipcio de El Cairo.

- Papiro de Ja: se encuentra en el Museo Egipcio de Turín, tiene 33 capítulos.

- Papiro de Nu: se encuentra en el Museo Británico (nº 10.477) y posee 137 capítulos.

Bibliografía [editar]

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (2007), El libro egipcio de los muertos, Málaga: Editorial Sirio. ISBN 8478085327.

- Lara Peinado, Federico (1989 (4ª edición 2005)), Libro de los Muertos, Madrid: Editorial Tecnos. ISBN 8430943439.

Véase también [editar]

- Libro del Amduat

- Libro de las Cavernas

- Libro de las Puertas

- Textos de las Pirámides

- Textos de los Sarcófagos

Enlaces externos [editar]

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Libro de los Muertos.Commons

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Libro de los Muertos.Commons- Budge, E. A. Wallis. El Libro de los Muertos (en inglés) en el Proyecto Gutenberg.

Textos jeroglíficos editados de numerosos papiros (bajo dominio público):

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The book of the Dead. The chapters of coming forth by day, Volume 1. Londres, 1898. (en inglés: PDF 9965 Kb)

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The book of the Dead. The chapters of coming forth by day, Volume 2. Londres, 1898. (en inglés: PDF 13.956 Kb)

Languages

- Afrikaans

- Brezhoneg

- Български

- Català

- Česky

- Deutsch

- Ελληνικά

- Español

- Esperanto

- Français

- Hrvatski

- Galego

- Italiano

- עברית

- Lietuvių

- Magyar

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk (bokmål)

- Polski

- Português

- Русский

- Simple English

- Slovenščina

- Srpskohrvatski / Српскохрватски

- Svenska

- ไทย

- Türkçe

- 中文

Butterfly Art Series

Templo de Konsu en Karnak

artehistoriacom

Los dos monumentos que más importan a los egipcios son el templo y el sepulcro. Los templos son las casas de piedra eterna que los faraones construyen para sus divinos padres.

Durante la historia de Egipto se han construido diferentes tipos de templo pero el de Konsu en Karnak será considerado el prototipo.

Antes de acceder al templo, el visitante recorre una larga avenida flanqueada a ambos lados por estatuas de animales divinos, carneros de Amón o esfinges. Se denomina por esto la avenida de las esfinges. Al fondo de ésta se levanta la gran fachada exterior del templo denominada pilono. Está construida en talud, formando una figura trapezoidal y en el centro se sitúa la puerta de acceso, también en forma de trapecio. En dos hendiduras talladas en la parte inferior del pilono se colocan los mástiles. Delante del pilono se ubican los obeliscos cubiertos de inscripciones.

Una vez franqueada la puerta se encuentra la sala hipetra, patio cubierto con columnas en los laterales y el fondo, ampliadas a los cuatro frentes en época saíta. A continuación se halla la sala hipóstila, sala de columnas totalmente cubierta, con la nave central más elevada que las restantes y con claraboyas laterales en el desnivel. Al fondo, rodeado de corredores y habitaciones, se sitúa el sancta-sanctorum, sala donde se venera la divinidad y a la que sólo pueden acceder el sacerdote y el faraón.

El edificio se dispone alrededor de un eje y las salas manifiestan una progresiva oscuridad y disminución de altura. Cada espacio está destinado a un grupo social. En la avenida de las esfinges se situaría el pueblo, en la sala hipetra los nobles, en la hipóstila la familia real y en el santuario el faraón.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario