KV62

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Contenido

| KV62 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tutanjamón |

| Ubicación | Valle de los Reyes | |

| Descubierta | 4 de noviembre 1922 | |

| Excavada por | Howard Carter | |

| Altura max. | 3,68 m | |

| Anchura max. | 7,86 m | |

| Longitud | 30,79 m | |

| Área | 109,83 m² | |

| Anterior : KV61 | Siguiente : KV63 |

La tumba KV62, situada en el Valle de los Reyes (Egipto), es la única tumba real egipcia encontrada intacta, y la mejor conservada. En ella se depositó el cuerpo de Tutankamón, faraón de la decimoctava dinastía. Fue descubierta en 1922 por Howard Carter bajo los restos de las viviendas de los trabajadores de la época ramésida, lo que la salvó de los saqueos de ese periodo. Como dato curioso, Carter consiguió fotografiar algunas ofrendas florales que se desintegraron al tocarlas.

La tumba consta de cuatro salas y estaba llena de objetos, pero en desorden. Debido a su estado y a al método meticuloso de estudio de Carter, se tardó ocho años en vaciarla y trasladar al Museo Egipcio de El Cairo todo lo encontrado, más de 5.000 piezas, incluida la máscara funeraria de Tutankamon de oro macizo.

Se dice a menudo que la tumba de Tutanjamón nunca fue violada, pero esto no es exacto. De hecho lo fue por lo menos dos veces no mucho después del entierro: hay evidencias de que en las puertas selladas se practicó una abertura en las esquinas superiores, que fue precintada de nuevo más adelante. Se ha estimado que el 60% de las joyas depositadas en la llamada "Tesorería" fueron robadas, y que los funcionarios de la necrópolis embalaron las que se salvaron de forma precipitada.[1] Las puertas exteriores de las capillas, que incluían los ataúdes jerarquizados del rey, se dejaron abiertas y sin sellar.

Parece ser que, tras uno de los robos, algunos artículos de la KV62 se depositaron en la KV54.

Contenido |

Descubrimiento [editar]

En 1907, justo antes del descubrimiento de la tumba de Horemheb, el equipo de Theodore M. Davis encontró una pequeña cámara, la llamada KV54, conteniendo objetos funerarios con el nombre de Tutanjamón. Pensando que era la tumba de este faraón, Davis concluyó la excavación.[2]

El arqueólogo británico Howard Carter (a las órdenes de Lord Carnarvon) descubrió la tumba de Tutanjamón en el Valle de los reyes el 4 de noviembre de 1922, cerca de la entrada de la de Ramsés VI, la KV35. El hallazgo renovó el interés del mundo occidental por la egiptología. Carter avisó a Carnarvon y el 26 de noviembre ambos hombres fueron los primeros en entrar en la tumba en 3000 años. Tras semanas de una excavación cuidadosa, el 16 de febrero de 1923, Carter abrió la cámara interior y descubrió el sarcófago del faraón.

Desde que apareció el primer tramo de escalera el 4 de noviembre de 1922, el avance de la excavación fue lento y minucioso, concluyendo el 8 de noviembre de 1930, fecha en que se sacaron los últimos objetos.[3]

Leyenda del plano adjunto:

|

|

|

Descripción [editar]

La tumba no parece haber sido diseñada para un faraón, parece la de un noble que haya sido adaptada de forma precipitada, como indica el hecho de que sólo fueron pintadas las paredes de la cámara del sarcófago, a diferencia de otras tumbas reales en que todos sus muros tienen escenas del Libro de los muertos.[4]

Acceso [editar]

La escalera de acceso parte de una pequeña plataforma y consta de 16 escalones que llevan a la primera puerta sellada y enyesada, con muestras de haber sido violada y vuelta a sellar en dos ocasiones.

Corredor y antecámara [editar]

Más allá del primer umbral, un pasillo descendente conduce a una segunda puerta sellada, y tras ella a la sala que Carter llamó «antecámara». Fue utilizada originalmente para depositar el material del embalsamamiento del rey, que tras los robos fue trasladado al interior de la tumba o a la KV54.

Las paredes están sin decorar; Carter la describió como «un caos organizado». Contenía más de 600 objetos entre los que había tres camas fúnebres, placas con forma de hipopótamo representando a Tueris, de vaca (Hathor) y de leopardo. También se encontraban cuatro carros desmontados, uno para caza, otro de guerra y dos destinados a los desfiles.

Sobre la pared de derecha, al fondo, rastros de excavación abandonada indican que se pensaba ampliar hacia el norte unos dos metros. Al principio de esta pared se encuentra acceso a la cámara funeraria, cuyas características informan también de la apertura proyectada.

Anexo [editar]

A la izquierda de la pared del fondo de la antecámara, hay un pequeño paso, rodeado con trazos negros que delimitan la apertura que habría de tener la puerta una vez terminada, que permite el acceso a otra habitación cuyo suelo tiene un nivel de 90 cm por debajo de la anterior. Llamada «anexo» por Carter, éste describió la existencia de trazos rojos sobre las paredes. Contenía, en desorden, cestas, jarras de vino, una vajilla de calcita, perfumes, maquetas de barcos y ushebtis: 280 grupos de objetos que sumaban en total dos mil piezas.

Cámara del sarcófago [editar]

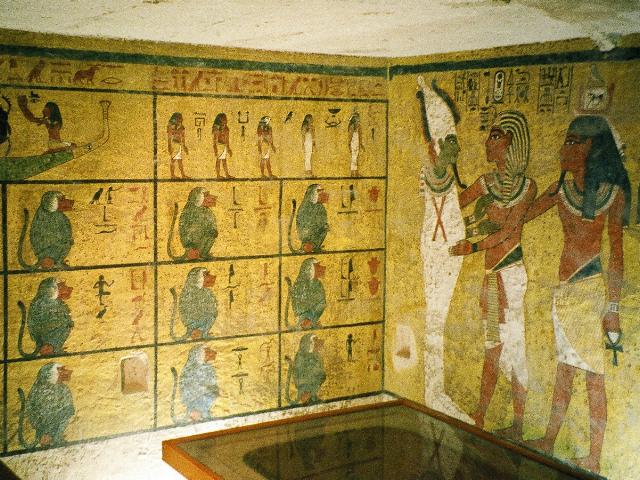

Esta habitación está situada con un desnivel de un metro y contenía 300 objetos además del sarcófago situado en el centro. Es la única decorada, y cada una de las paredes, enyesadas y pintadas, simulan nichos con distintas escenas cuyo fondo es amarillo oro, en un estilo diferente al tradicional decorado de las tumbas. Representan escenas del Libro de los muertos:

- Pared de la derecha, Anubis, Isis y Hathor;

- Pared del fondo, están Nut y Tutanjamón que, seguido por su Ka, es llevado al reino de los muertos por Osiris;

- Pared de la izquierda, Ay en funciones de sacerdote está practicando el ritual de la apertura de la boca.

Cuatro capillas de madera recubiertas de oro, encajadas una en otra, cubrían un sarcófago de cuarcita roja que contenía tres ataúdes momiformes, de madera chapada de láminas de oro los dos primeros y de oro macizo el tercero. Dentro descansaba la momia del joven faraón, con la cabeza y los hombros cubiertos por la célebre máscara.

La capilla externa mide 5,08 x 3,28 x 2,75 m y 32 milímetros de grosor, ocupaba casi toda la cámara dejando libres 60 cm a los extremos y menos de 30 en los costados.

La cuarta capilla tiene 2,90 m de largo y 1,48 m de ancho. Las paredes fueron adornadas con la procesión fúnebre del rey, y en su techo estaba Nut, abrazando con sus alas el sarcófago externo.[5]

Fuera de las capillas había once remos para la "barca solar", frascos de perfumes, lámparas decoradas con el dios Hapy y el Templete canópico de Tutankamon, cuyos cuatro lados están decorados con imágenes de las diosas Isis, Neftis, Serket y Neit, y que contenía el cofre, que a su vez albergaba los cuatro vasos canopos con las vísceras del faraón.

Cámara del Tesoro [editar]

Otra pequeña habitación, llamada «cámara del tesoro» por Carter, contenía alrededor de 500 objetos.

Notas [editar]

- ↑ De hecho, se equivocaron al rotularlas, según las inscripciones que dejaron en las cajas.

- ↑ En 1912 Davis publicó detalles de ambas búsquedas, en las que afirmaba Me temo que el Valle de los Reyes está ya agotado. (Davis, Theodore M. (2001). The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou. Duckworth Publishing. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.)

- ↑ Diarios de Howard Carter (1922-1930). «Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation» (en inglés). Consultado el 06, 12 de 2007.

- ↑ American University El Cairo (2006). «Theban Mapping Project» (en inglés). Consultado el 06, 12 de 2007.

- ↑ esquema de las capillas.

Enlaces externos [editar]

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre KV62. Commons

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre KV62. Commons- Moreno, Julia y López, M. A. «KV62» (en español). El magnífico Valle de los Reyes. Consultado el 07, 12 de 2007.

- Conde Torrens, Fernando. «El tesoro de Tutankhamon» (en español). Consultado el 07, 12 de 2007.

Categoría: Valle de los Reyes

KV62

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Contenido

| KV62 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Burial site of Tutankhamun | ||

| Location | East Valley of the Kings | |

| Discovery Date | 4 November 1922 | |

| Excavated by | Howard Carter | |

| Decoration | Opening of the Mouth ritual, Amduat, Book of the Dead | |

| Previous : KV61 | Next : KV63 | |

KV62 is the tomb of Tutankhamun in the Valley of the Kings (Egypt) , which became famous for the wealth of treasure it contained.[1] The tomb was discovered in 1922 by Howard Carter, underneath the remains of workmen's huts built during the Ramesside Period; this explains why it was spared from the worst of the tomb depredations of that time. KV is an abbreviation for the Valley of the Kings, followed by a number to designate individual tombs in the Valley.

The tomb was densely packed with items in great disarray. Carter was able to photograph garlands of flowers, which disintegrated when touched. Due to the state of the tomb, and to Carter's meticulous recording technique, the tomb took nearly a decade to empty, the contents all being transported to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

Tutankhamun's tomb had been entered at least twice, not long after he was buried and well before Carter's discovery. The outermost doors of the shrines enclosing the king's nested coffins were left opened, and unsealed. It is estimated that 60% of the jewellery which had been stored in the "Treasury" was removed as well. After one of these ancient robberies, embalming materials from KV62 are believed to have been buried at KV54.

Contents |

[edit] Discovery of the tomb

In 1907, just before his discovery of the tomb of Horemheb, Theodore M. Davis's team uncovered a small site containing funerary artifacts with Tutankhamun's name. Assuming that this site, identified as KV54, was Tutankhamun's complete tomb, Davis concluded the dig. The details of both findings are documented in Davis's 1912 publication, The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou; the book closes with the comment, "I fear that the Valley of Kings is now exhausted."[2] But Davis was to be proven spectacularly wrong.

The British Egyptologist Howard Carter (employed by Lord Carnarvon) discovered Tutankhamun's tomb (since designated KV62) in the Valley of the Kings on November 4, 1922, near the entrance to the tomb of Ramesses VI, thereby setting off a renewed interest in all things Egyptian in the modern world. Carter contacted his patron, and on November 26 that year, both men became the first people to enter Tutankhamun's tomb in over 3000 years. After many weeks of careful excavation, on February 16, 1923, Carter opened the inner chamber and first saw the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. All of this was conveyed to the public by H. V. Morton, the only journalist allowed on the scene.

[edit] Investigation

The first step to the stairs was found on November 4, 1922.[3] The following day saw the exposure of a complete staircase. The end of November saw access to the Antechamber and the discovery of the Annex, and then the Burial Chamber and Treasury.

On November 29, the tomb was officially opened, and the first announcement and press conference followed the next day, The first item was removed from the tomb on December 27.[4]

February 16, 1923 saw the official opening of the Burial Chamber[5], and April 5 saw the death of Lord Carnarvon.

On February 12, 1924, the granite lid of the sarcophagus was raised.[6] In April, Carter argued with the Antiquities Service, and left the excavation for the United States.

In January 1925, Carter resumed activities in the tomb, and on October 13, he removed the cover of the first sarcophagus; on October 23, he removed the cover of the second sarcophagus; on October 28, the team removed the cover of the final sarcophagus and exposed the mummy; and on November 11, the examination of the remains of Tutankhamun started.

Work started in the Treasury on October 24, 1926, and between October 30 and December 15, 1927, the Annex was emptied and examined.

On November 10, 1930, eight years after the discovery, the last objects were finally removed from the tomb of the long lost Pharaoh.[7]

[edit] Layout of tomb

In design, the tomb appears to have originally been intended for a private individual, not for royalty.[8] There is some evidence to suggest that the tomb was adapted for a royal occupant during its excavation.[9] This may be supported by the fact that only the burial chamber walls were decorated, unlike royal tombs in which nearly all walls were painted with scenes from the Book of the Dead.[9]

[edit] Staircase

Starting from a small, level platform, 16 steps descend to the first doorway, which was sealed and plastered – although it had been penetrated by grave robbers at least twice.

[edit] Entrance corridor

Beyond the first doorway, a descending corridor leads to the second sealed door, and into the room that Carter described as the Antechamber. This was used originally to hold material left over from the funeral and material associated with the embalming of the king, after the initial robberies this material was either moved into the tomb proper, or moved to KV54.

[edit] Antechamber

The undecorated Antechamber was found to be in a state of "organized chaos" and contained approximately 700 objects (articles 14 to 171 in the Carter catalogue) amongst which were three funeral beds, plates in shape of Hippopotamus (the Goddess Tawaret), of lion (or leopards) and cattle (the Goddess Hathor). Perhaps the most remarkable item in this room were the components, stacked, of four chariots of which one was probably used for hunting, one for "war" and another two for parades.

[edit] Burial chamber

[edit] Decoration

This is the only decorated chamber in the tomb, with scenes from the Opening of the Mouth ritual (showing Ay, Tutankhamun's successor acting as the king's son, despite being older than him) and Tutankhamun with the goddess Nut on the north wall, the first hour of Amduat (on the west wall), spell one of the Book of the Dead (on the east wall) and representations of the king with various deities (Anubis, Isis, Hathor and others now destroyed) on the south wall. The north wall shows Tutankhamen being followed by his Ka, being welcomed to the underworld by Osiris.[10]

[edit] Contents

The entire chamber was occupied by a series of gilded wooden shrines which surrounded the king's sarcophagus. The outer shrine ([1] in the cross-section) measured 5.08 x 3.28 x 2.75 m and 32 mm thick, almost entirely filling the room, with only 60 cm at either end and less than 30 cm on the sides. Outside of the shrines were 11 paddles for the "solar boat", containers for scents, lamps decorated images of the God Hapi.

The fourth and last shrine ([4]) was 2.90 m long and 1.48 m wide. The walls were decorated by the king's funeral procession, and Nut was painted on the ceiling, "embracing" with her wings the sarcophagus.

This sarcophagus was constructed in granite ([a] in the cross-section). The main body and the lid were carved from different coloured stone at each corner, it appears to have been constructed for a different owner, but then recarved for Tutankhamen, the identity of the original owner is not preserved.[10] In each corner a protective goddess (Isis, Nephthys, Serket and Neith) guards the body.

Inside the king's body was placed within three mummiform coffins, the outer two made of gilded wood while the innermost was composed of 110.4 kg of pure gold.[11] The mummy itself was adorned with a gold mask, mummy bands and other funerary items. The funerary mask was made of gold, inlaid with lapis lazuli, carnelian, quartz, obsidian, turquoise and glass and faience and weighed 11 kg.[12]

[edit] Treasury

The treasury was the burial chamber's only side-room and was accessible by an unblocked doorway. It contained over 500 objects, most of them funerary and ritual in nature. The two largest objects found in this room were the king's elaborate canopic chest and a large statue of Anubis. Other items included numerous shrines containing gilded statuettes of the king and deities, model boats and two more chariots. This room also held two mummies of foetuses that some consider to have been stillborn offspring of the King.[13]

[edit] Annex

The 'Annex', originally used to store oils, ointments, scents, foods and wine, was the last room to be cleared, from the end of October 1927 to the spring of 1928. Although quite small in size, it contained approximately 280 groups of objects, totaling more than 2,000 individual pieces.

[edit] Present day

As of 2007, the tomb is open for visitors, at an additional charge above that of the price of general access to the Valley of the Kings. The number of visitors is limited to 400 per day, as of May 2008.[14]

As of 2009, an online recreation of KV62 can also be explored via the Heritage Key virtual experience.

[edit] Bibliography

- The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamen, by Howard Carter, Arthur C. Mace.

- The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure, by C. N. Reeves, Nicholas Reeves, Richard H. Wilkinson.

- Reeves, N & Wilkinson, R.H. The Complete Valley of the Kings, 1996, Thames and Hudson, London

- Siliotti, A. Guide to the Valley of the Kings and to the Theban Necropolises and Temples, 1996, A.A. Gaddis, Cairo

[edit] References

- ^ "Tutankhamun". University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/chronology/tutankhamun.html. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Davis, Theodore M. (2001). The Tombs of Harmhabi and Touatânkhamanou. London: Duckworth Publishing. ISBN 0-7156-3072-5.

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (October 28 to December 30 1922)". http://griffith.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/gri/4sea1not.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "A. C. Mace's personal diary of the first excavation season (December 27, 1922 to May 13, 1923)". http://griffith.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/gri/4macedia.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (January 1 to May 31, 1923)". http://www.ashmolean.museum/gri/4sea1no2.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (October 3, 1923 to February 11, 1924)". http://www.ashmolean.museum/gri/4sea2not.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "Howard Carter's diaries (September 24 to November 10, 1930)". http://griffith.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/gri/4sea9not.html. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ "KV 62 (Tutankhamen)". http://www.thebanmappingproject.com/sites/browse_tomb_876.html. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ a b Reeves & Wilkinson (1996) p.124

- ^ a b "KV 62 (Tutankhamen): Burial chamber J". http://www.thebanmappingproject.com/sites/browse_component_396.html. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ "Note concerning the 3rd Coffin". http://griffith.ashmus.ox.ac.uk/gri/tut-files/TAA_i_3_10_2.html. Retrieved 2007-06-10.

- ^ Alessandro Bongioanni & Maria Croce (ed.), The Treasures of Ancient Egypt: From the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, Universe Publishing, a division of Ruzzoli Publications Inc., 2003. p.310

- ^ Howard Carter, "The Tomb of Tutankhamen", 1972 ed, Barrie & Jenkins, p189, ISBN 0-214-65428-1

- ^ "400 visitors to Tutankhamun's tomb". Egypt State Information Service. http://www.sis.gov.eg/En/EgyptOnline/Culture/000001/0203000000000000000872.htm. Retrieved 2007-11-13.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: KV62 |

- Plans of the tomb and other details Theban Mapping Project

- Burton's images of the tomb from The Howard Carter Archives Griffith Institute

- Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation Griffith Institute

Coordinates: 25°44′25.30″N 32°36′05.20″E / 25.740361°N 32.601444°E

| |||||||||||

related articles

Languages

- বাংলা

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Español

- Français

- Galego

- Italiano

- Magyar

- Nederlands

- Norsk (bokmål)

- Português

- Suomi

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

Category:KV62

From Wikimedia Commons, the free media repository

Contenido

KV62 is the tomb of Tutankhamun, in the Valley of the Kings.

Subcategories

This category has only the following subcategory.

T

- [+] Treasure of Tutankhamun (67 F)

Media in category "KV62"

The following 16 files are in this category, out of 16 total.

Babo Tut.JPG 264,496 bytes | Carnarvon.jpg 30,667 bytes | Egypt.KV62.01.jpg 82,383 bytes |

Howard Carter in the... 94,305 bytes | Map of the Tomb of T... 14,376 bytes | Opening of the Mouth... 76,184 bytes |

The Moment Carter Op... 4,449,448 bytes | Tomb of Tutankhamun ... 1,421,501 bytes | Tutanhamon002.jpg 30,090 bytes |

Tutankhamen KV62.jpg 64,506 bytes | Tutankhamen Tomb lay... 135,324 bytes | Tutankhamen tomb lay... 91,162 bytes |

Tutankhamun Valley o... 560,236 bytes | Tutankhamun'sAncestr... 256,667 bytes | Tuts Tomb Opened.JPG 207,164 bytes |

VallDelsReisTutankha... 336,365 bytes |

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario