| |

Galeria de Hans Ollermann

Deir el-Medina.

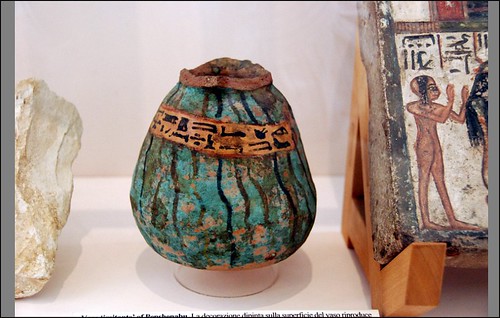

2008_0610_160648AA Egyptian Museum, Turin

Terracotta vase of Penshenabu.

Deir el-Medina.

Dynasty XIX (1292-1186 B.C.)

Egyptian Museum, Turin.

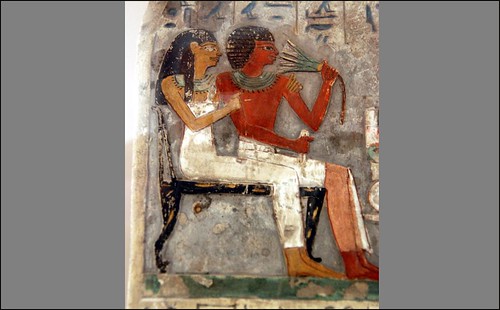

2008_0610_160835AA Egyptian Museum, Turin

Stele of a married couple.

Deir el-Medina.

Dynasty XVIII-XX (1550-1070 B.C).. Egyptian Museum, Turin.

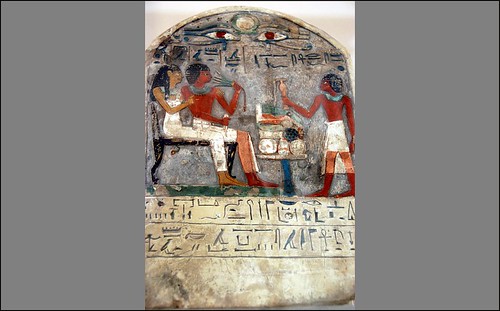

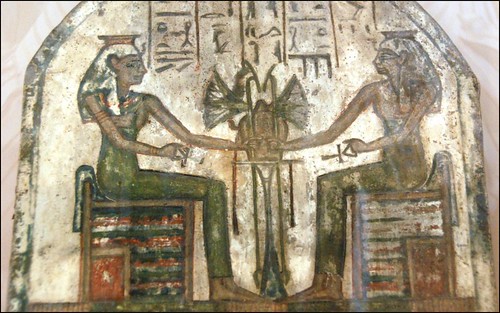

2008_0610_160824AA Egyptian Museum, Turin

Stele of a married couple.

Deir el-Medina.

Dynasty XVIII-XX (1550-1070 B.C).. Egyptian Museum, Turin.

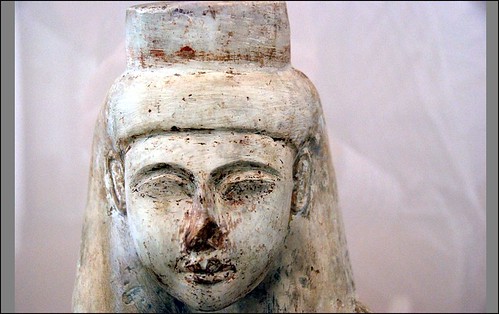

2008_0610_160300AA Egyptian Museum, Turin

Statue o tMeretseger, the protector-goddess of the necropolis

Detail.

Deir el-Medina.

Dynasty XIX-XX (1292-1070 B.C.)

Egyptian Museum, Turin.

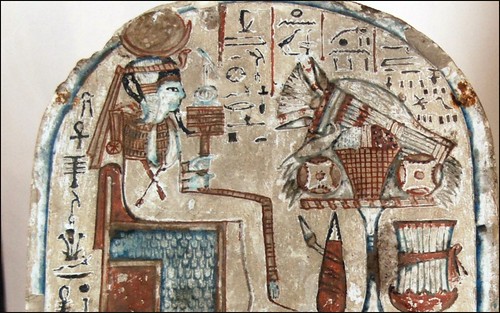

2008_0610_160712AA Egyptian Museum, Turin

Round-topped stele of Pendua and his wife Tyr.

The couple wear clothes and hairstyles of the period, while their children are naked as reference to their young age.

Limestone.

Deir el-Medina.

Dynasty XIX (1292-1186 B.C.)

Egyptian Museum, Turin.

2008_0610_160853AA Egyptian Museum, Turin-

Stele dedicated to Khonsu.

Detail.

The scribe and draftsman Nebra and his son Amenemipet recite a prayer to the moongod Khonsu, son of Amun, patron of Thebes.

Limestone.

Deir el-Medina.

Dynasty XIX (1292-1186 B.C.)

Egyptian Museum, Turin.

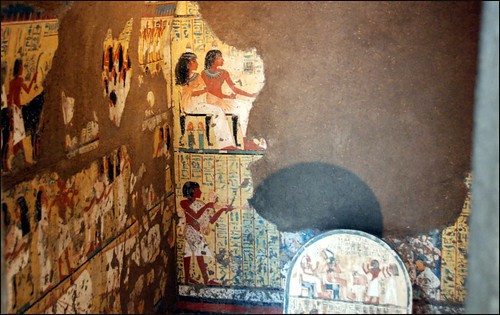

2008_0610_164921AA Egyptian Museum, Turin

Reconstruction of the Chapel of Kha.

Kha's vaulted chapel was sited in a pyramidal superstructure some distance from the shaft of the tomb, whose contence are displayed in the Turin Museum.

The chapel and its decoration are still in situ in Deir el-Medina.

Egyptian Museum, Turin.

Tomb of Kha and his wife Merit.

Kha was architect of the Pharaoh (Amenhotep II 18th Dynasty) and responsible for building projects not just in the reign of Amenhotep II, but also in the reign of 3 or 4 kings: Tuthmosis III, Amenhotep II, Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III

The intact tomb was discovered by E. Schiaparelli in 1906.

The access shaft to the funerary chamber was neither located in the chapel nor in the courtyard, but at a certain distance from both.

The collapse of a nearby Ramesside tomb had hidden it completely, thus preserving the burial intact through the course of 33 centuries.

A staircase led to a corridor and ante-chamber.

The funerary provisions were placed here because there was no room in the burial chamber itself at the time of the burial.

A bed, two baskets, two amphora's and a chair were also in this ante-chamber.

The entrance to the funeral chamber was blocked by a heavy wooden door that was closed on the in-side.

The chamber itself was rectangular with smooth plastered walls.

The great rectangular sarcophagi were inside, placed along the walls and covered with linen sheets.

A statue of Kha was on a chair, which stood in front of the sarcophagus of Merit.

It was garlanded with flowers.

Comentários

Lenka P  disse:

disse:

This is interesting, Hans, I did not know it was there. Thank you. Postado 20 meses atrás. ( permalink )

---------- Mensaje Original -----------------

De: Mª Isabel Pina Noé [pinanoe@hotmail.com]

Para: amigosegiptologia@listserv.rediris.es

-------------------------------------------

Buenas tardes,

Quería dar las gracias a Javier Uriach por haber pasado el artículo completo. Se agradece que las personas que pueden acceder a este tipo de archivos nos hagan el favor de ponerlos accesibles al resto, no entendidos pero muy interesados en la materia.

Gracias de nuevo y un saludo cordial a todos.

Isabel Pina Noé

-

Envío adjunto el artículo completo de JAMA gentileza de Javier Uriach:

Un saludo

Víctor Rivas

Coordinador General de AE

egiptologia@egiptologia.com

Re: [AE-ES] RV: [AE] Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Holas!

Mamen

viernes 19 de febrero de 2010

Re: [AE-ES] [AMIGOSEGIPTOLOGIA] Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

resultado de los últimos estudios realizados en su momia. Para este trabajo, hemos recurrido a las imágenes de la TAC que se le realizó hace unos años. Muchas gracias.

Un abrazo,

Instituto de Estudios Científicos en Momias (IECIM)

------------

http://www.facebook.com/inbox/?tid=419036555075#/pages/Instituto-de-Estudios-Cientificos-en-Momias/140490073140?ref=ts

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XN-_kiI7aZ4&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dwnNWvtggdA

viernes 19 de febrero de 2010

Re: [AE-ES] [AMIGOSEGIPTOLOGIA] Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Pere Simó

viernes 19 de febrero de 2010

Re: [AE-ES] [AMIGOSEGIPTOLOGIA] Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family

Estoy hablando de memoria y no encuentro la imagen.

La buscaré

Saludos

Laura Di Nóbile

Centro de Estudios Artísticos Elba

www.centroelba.es

http://centroelba.blogspot.com

http://centroelba-cursos.blogspot.com

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Madrid/Centro-de-Estudios-Artisticos-Elba/148621500080

http://www.myspace.com/centroelba

http://twitter.com/CentroElba

http://www.youtube.com/centroelba

Access

http://www.nature.com/news/2010/100216/full/news.2010.75.htmlAccess

This article is part of Nature's premium content.

Published online 16 February 2010 | Nature | doi:10.1038/news.2010.75

News

King Tut's death explained?

Experts question claims that malaria and osteonecrosis contributed to Pharaoh's decline.

A research team says it has solved the mystery surrounding the death of the Egyptian boy-king Tutankhamun, who died in about 1324 B.C. at the age of 19.

To read this story in full you will need to login or make a payment (see right).

Comments

If you find something abusive or inappropriate or which does not otherwise comply with our Terms or Community Guidelines, please select the relevant 'Report this comment' link.

Comments on this thread are vetted after posting.

- #9520

See Nov '09 New Yorker for a lengthy but not flattering article on paper's author, Dr. Hawass. Fairly sure same person.

- Report this comment

- 2010-02-18 05:51:33 PM

- Posted by: shane miller

- #9526

Note that Mark Rose, online editorial director of the American Institute of Archeology has serious doubts about the identification of mummy KV55 as Akhenaten (www.archaeology.org/online/features/tutdna). He states that this mummy died died in the 20's while Akhenaten must have been in his 30's at death. He suggest that KV55 may be Tut's brother and may be Smenkhkare. Tut's mother still may be Kiya, a secondary wife of Akhenaten, but, if so, her origin cannot be as foreign as once thought. More details at the website cited.

- Report this comment

- 2010-02-19 09:31:20 AM

![[image]](http://www.archaeology.org/1003/cover_sm.gif)

News reports are coming out today about Tut, malaria, and his family DNA. Here's a quick take based on an early cut of the Discovery documentary and the Journal of the American Medical Association press release.

The bone degeneration in one of Tut's feet is very clear. Genetic evidence of malaria is said to have been found in Tut's mummy and three others. The researchers speculate that bone degeneration and a broken leg plus malaria might have done Tut in. Some of the versions of the story suggest that Tut was "frail," a view that runs counter to our March/April cover story, "Warrior Tut." I suspect that they are overdoing it a bit.

The positive identification of the mummy from tomb KV55 as Akhenaten--thought by many to be Tut's father--is a little puzzling as the mummy's age at death estimated osteologically and dentally is too young. The individual was perhaps just a bit older than 20, while mid-30s is what we'd expect for Akhenaten. It isn't clear to me that identification of KV55 as Smenkhkare, possibly Tut's brother, can be ruled on the DNA results. (I've emailed the project's DNA specialist about this point.)

Somewhat startlingly, the so-called "Younger Lady" mummy from KV35 is said to be Tut'mother. Many believe he was the son of Akhenaten and Nefertiti. This identification was suggested years ago by Marianne Luban in 1999, then controversially was repeated by Joann Fletcher in her book The Search for Nefertiti. Fletcher's work was seen as problematic and many Egyptologists rejected it. Among them was Dr. Zahi Hawass, then secretary general of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), who labeled the idea "pure fiction." See my review of The Search for Nefertiti for details. I suppose they could say it was Kiya, a prominent secondary queen. Some think Kiya was a foreign princess, but the Tut family tree on the Discovery website here suggests the KV55 and KV35 Younger Lady are blood relations. So...

Less unexpected is the identification of the "Elder Lady" mummy in KV35 as Queen Tiye, Tutankhamun's grandmother. This had long been thought a good possibility.

The Discovery documentary that shows some of this research is set to air Sunday, February 21, at 8 PM (ET/PT) and Monday, February 22, at 8 PM (ET/PT). Hopefully the full paper in JAMA goes into the DNA analysis and handling procedures in depth.

![[image]](http://www.archaeology.org/online/reviews/nefertiti/thumbnails/mummy1.gif) | ![[image]](http://www.archaeology.org/online/reviews/nefertiti/thumbnails/mummy2.gif) |

| The Elder Woman from KV35 is thought to be Queen Tiye. | The Younger Woman from KV35, now claimed to be Tut's mom |

Mark Rose is AIA Online Editorial Director.

See also

- Warrior Tut: Sculptures from Luxor prove the "Boy King" was the scourge of Egypt's foes

- Where's Nefertiti?: Joann Fletcher's The Search for Nefertiti makes a big claim

- TutWatch: After a more than a quarter-century, Tutankhamun returns to the U.S.

The Tut Puzzle

- Analysis by Rossella Lorenzi | Tue Feb 16, 2010 02:42 PM ET

King Tut, the best-known pharaoh of ancient Egypt, has been puzzling scientists ever since his mummy- and treasure-packed tomb were discovered in 1922 the Valley of the Kings by British archaeologist Howard Carter.

Only a few facts about his life are known.

While he lived in Amarna, his name was Tutankhaton ("honoring Aton" -- the sun god).

When he ascended the throne in 1333 B.C., at the age of nine, and moved to Thebes, he changed his name to Tutankamun ("honoring Amun" -- a traditional cult).

He married 13-year-old Ankhesenpaaten, the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, on his accession to the throne and reigned until his death in 1325 B.C., aged 19.

He was a pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, probably the greatest of the Egyptian royal families.

He has been believed to be either the son of the minor king Smenkhkare or the offspring of Amenhotep III, the father of the "heretic" pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 B.C.)

Another leading theory suggested that King Tut was sired by Akhenaten, the revolutionary pharoah who established the capital of his kingdom in Amarna, introducing a monotheistic religion that overthrew the pantheon of the gods to worship the sun god Aton.

Doubts also remain about King Tut's mother. Scholars have long debated whether he is the son of Kiya, Akhenaten's minor wife, or Queen Nefertiti, Akhenaten's other wife.

Evidence that Tutankhamun was the child of Akhenaten has come from an inscribed limestone block pieced together by Hawass in December 2008.

The block shows the young Tutankhamun and his wife, Ankhesenamun, seated together. The text identifies Tutankhamun as the "king's son of his body, Tutankhaten," and his wife as the "king's daughter of his body, Ankhesenaten.”

According to Hawass, "the only king to whom the text could refer as the father of both children is Akhenaten."

Egyptologists also debated whether two fetuses found in his tomb were the stillborn children of King Tut and his wife Ankhesenpaaten, who had changed her name to Ankhesenamun, or if they were placed in the tomb with the symbolic purpose of allowing the boy king to live as newborns in the afterlife.

A series of X-rays taken by British scientist Ronald Harrison in 1968 revealed a bone fragment in his skull, prompting speculation that a blow to the head killed the boy pharaoh.

In 2005 the mummy underwent a series of CT scans, which revealed that the fragments were not broken because of an injury incurred before death, but during the embalming process.

It also ruled out that the boy pharaoh crushed his chest when falling from his chariot, as suggested by American Egyptologist Denis Forbes.

While establishing that the boy king was about 1.70 metres (4 feet, 9 inches) tall, the CT scan showed that the king had a small cleft in his hard palette, the lower teeth slightly misaligned, and the overbite characteristic of other kings of from his family.

It rejected the diagnosis of an abnormal curvature of the spine and fusion of the upper vertebrae, which would have indicated King Tut suffered from a rare disorder called Klippel-Feil syndrome, a condition often associated with scoliosis which makes sufferers look as if they have a short neck.

The most important anomaly was a fracture of the left lower femur (thighbone). Some members of the team who examined the 17,000 images of the CT scan, suggested that King Tut suffered an accident in which he broke his leg badly, leaving an open wound, with infection setting in.

Other members of the team believed it was also possible that the fracture was caused by the embalmers.

In 2007, a black, leathery, shriveled and cracked King Tut emerged with a toothy smile from his sarcophagus, showing his face to the world for the first time.

The rest of the body, which despite restoration work carried out over the past two years resembles a badly burnt skeleton, remain covered with beige linen.##########################################

RSS Feed de Amigos de la Egiptología

http://www.egiptologia.com/index.php?format=feed&TYPE=rss

##########################################

Noticias y Actualidad Egiptológica

http://www.egiptologia.com/noticias.html

Recomendamos: Sociedad Catalana de Egiptología

http://www.egiptologia.com/societat-catalana-de-egiptologia.html

--------------------------------------------------------------

LISTA DE DISTRIBUCIÓN DE AMIGOS DE LA EGIPTOLOGÍA - AE

Gestión Altas-Bajas y consulta mensajes enviados:

http://www.egiptologia.com/lista-de-distribucion.html

Moderador: Víctor Rivas egiptologia@egiptologia.com

Amigos de la Egiptología: http://www.egiptologia.com

Los mensajes de Amigos de la Egiptología son distribuidos gracias al apoyo y colaboración técnica de RedIRIS Red Académica Española - http://www.rediris.es

JAMA 2010 Feb 17th.pdf

JAMA 2010 Feb 17th.pdf