Atlántida

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Atlántida (en griego antiguo Ατλαντίς νησος, Atlantis nesos, ‘isla de Atlantis’ ) es el nombre de una isla legendaria desaparecida en el mar, mencionada y descrita por primera vez en los diálogos Timeo y el Critias, textos del filósofo griego Platón.

La precisa descripción de los textos de Platón y el hecho que en ellos se afirme reiteradamente que se trata de una historia verdadera, ha llevado a que, especialmente a partir de la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, durante el Romanticismo, se propongan numerosas teorías sobre su ubicación. En la actualidad se piensa que el relato de la Atlántida, según la interpretación literal de las traducciones ortodoxas de los textos de Platón, presenta anacronismos y datos imposibles. Una opinión muy extendida es que la Atlántida descrita por Platón nunca existió, y que sólo es un mero vehículo literario o un mito inventado por él. Por otro lado, como ya se ha dicho, Platón describió el relato como historia verdadera y no como mito. Se ha apuntado que la leyenda pueda haber sido inspirada en un lejano fondo de realidad histórica, vinculado a alguna catástrofe natural pretérita como pudiera ser un diluvio, una gran inundación o un terremoto.

La Atlántida ha servido de inspiración para numerosas obras literarias y cinematográficas, especialmente historias de fantasía y ciencia-ficción.

Contenido |

El relato de Platón [editar]

El Timeo y el Critias [editar]

Las primeras referencias a la Atlántida aparecen en el Timeo y el Critias, textos en diálogos del filósofo griego Platón. En ellos, Critias, discípulo de Sócrates, cuenta una historia que de niño escuchó de su abuelo y que este, a su vez, supo de Solón, el venerado legislador ateniense, a quien se la habían contado sacerdotes egipcios en Sais, ciudad del delta del Nilo. La historia, que Critias narra como verdadera,[1] se remonta en el tiempo a nueve mil años antes de la época de Solón,[2] para narrar cómo los atenienses detuvieron el avance del imperio de los atlantes, belicosos habitantes de una gran isla llamada Atlántida, situada frente a las Columnas de Hércules y que, al poco tiempo de la victoria ateniense, desapareció en el mar a causa de un terremoto y de una gran inundación.

En el Timeo, Critias habla de la Atlántida en el contexto de un debate acerca de la sociedad ideal; cuenta cómo llegó a enterarse de la historia y cómo fue que Solón la escuchó de los sacerdotes egipcios; refiere la ubicación de la isla y la extensión de sus dominios en el mar Mediterráneo; la heroica victoria de los atenienses y, finalmente, cómo fue que el país de los atlantes se perdió en el mar. En el Critias, el relato se centra en la historia, geografía, organización y gobierno de la Atlántida, para luego comenzar a narrar cómo fue que los dioses decidieron castigar a los atlantes por su soberbia. Relato que se interrumpe abruptamente, quedando inconclusa la historia.

Descripción de la isla [editar]

Los textos de Platón sitúan la Atlántida frente a las Columnas de Hércules (lugar tradicionalmente entendido como el estrecho de Gibraltar) y la describen como una isla más grande que Libia y Asia juntas.[3] Se señala su geografía como escarpada, a excepción de una gran llanura de forma oblonga de 3000 por 2000 estadios, rodeada de montañas hasta el mar.[4] A mitad de la longitud de la llanura, el relato ubica una montaña baja de todas partes, distante 50 estadios del mar, destacando que fue el hogar de uno de los primeros habitantes de la isla, Evenor, nacido del suelo.[5]

Según el Critias, Evenor tuvo una hija llamada Clito. Cuenta este escrito que Poseidón era el amo y señor de las tierras atlantes, puesto que, cuando los dioses se habían repartido el mundo, la suerte había querido que a Poseidón le correspondiera, entre otros lugares, la Atlántida. He aquí la razón de su gran influencia en esta isla. Este dios se enamoró de Clito y para protegerla, o mantenerla cautiva, creó tres anillos de agua en torno de la montaña que habitaba su amada.[6] La pareja tuvo diez hijos, para los cuales el dios dividió la isla en respectivos diez reinos. Al hijo mayor, Atlas o Atlante, le entregó el reino que comprendía la montaña rodeada de círculos de agua, dándole, además, autoridad sobre sus hermanos. En honor a Atlas, la isla entera fue llamada Atlántida y el mar que la circundaba, Atlántico.[7] Un segundo hijo se llamaba Eumelo en griego, siendo su nombre original Gadiro, Gadeiron o Gadeirus, y gobernaba el extremo de la isla que se extiende desde las Columnas de Heracles hasta la región que, posiblemente por derivación de su nombre, se denominaba Gadírica, Gadeirikês o Gadeira en tiempos de Platón.[8]

Favorecida por Poseidón, la tierra insular de Atlántida era abundante en recursos. Había toda clase de minerales, destacando el oricalco, traducible como cobre de montaña, más valioso que el oro para los atlantes y con usos religiosos (actualmente se piensa que debía ser una aleación natural del cobre); grandes bosques que proporcionaban ilimitada madera; numerosos animales, domésticos y salvajes, especialmente elefantes; copiosos y variados alimentos provenientes de la tierra.[9] Tal prosperidad dio a los atlantes el impulso para construir grandes obras. Edificaron, sobre la montaña rodeada de círculos de agua, una espléndida acrópolis[10] plena de notables edificios, entre los que destacaban el Palacio Real y el templo de Poseidón.[11] Construyeron un gran canal, de 50 estadios de longitud, para comunicar la costa con el anillo de agua exterior que rodeaba la metrópolis; y otro menor y cubierto, para conectar el anillo exterior con la ciudadela.[12] Cada viaje hacia la ciudad era vigilado desde puertas y torres, y cada anillo estaba rodeado por un muro. Los muros estaban hechos de roca roja, blanca y negra sacada de los fosos, y recubiertos de latón, estaño y oricalco. Finalmente, cavaron, alrededor de la llanura oblonga, una gigantesca fosa a partir de la cual crearon una red de canales rectos, que irrigaron todo el territorio de la planicie.[13]

La caída del imperio atlante [editar]

Los reinos de la Atlántida formaban una confederación gobernada a través de leyes, las cuales se encontraban escritas en una columna de oricalco, en el Templo de Poseidón.[14] Las principales leyes eran aquellas que disponían que los distintos reyes debían ayudarse mutuamente, no atacarse unos a otros y tomar las decisiones concernientes a la guerra, y otras actividades comunes, por consenso y bajo la dirección de la estirpe de Atlas.[15] Alternadamente, cada cinco y seis años, los reyes se reunían para tomar acuerdos y para juzgar y sancionar a quienes de entre ellos habían incumplido las normas que los vinculaban.[14]

La justicia y la virtud eran propios del gobierno de la Atlántida, pero cuando la naturaleza divina de los reyes descendientes de Poseidón se vio disminuida, la soberbia y las ansias de dominación se volvieron características de los atlantes.[16] Según el Timeo, comenzaron una política de expansión que los llevó a controlar los pueblos de Libia (entendida tradicionalmente como el norte de África) hasta Egipto y de Europa, hasta Tirrenia (entendida tradicionalmente como Italia). Cuando trataron de someter a Grecia y Egipto, fueron derrotados por los atenienses.[17]

El Critias señala que los dioses decidieron castigar a los atlantes por su soberbia, pero el relato se interrumpe en el momento en que Zeus y los demás dioses se reúnen para determinar la sanción.[18] Sin embargo, habitualmente se suele asumir que el castigo fue un gran terremoto y una subsiguiente inundación que hizo desaparecer en el mar la isla donde se encontraba el reino o ciudad principal, "en un día y una noche terribles", según señala el Timeo.[19]

Recepción del relato de Platón hasta nuestros días [editar]

En la Antigüedad [editar]

Se conservan no pocos párrafos de escritores antiguos que aluden a los escritos de Platón sobre la Atlántida; ciertamente se han perdido muchos otros. Estrabón, en el siglo I a. C., parece compartir la opinión de Posidonio (c. 135-51 a. C.) acerca de que el relato de Platón no era una ficción.[20] Un siglo más tarde, Plinio el Viejo nos señala en su Historia Natural que, de dar crédito a Platón, deberíamos asumir que el océano Atlántico se llevó en el pasado extensas tierras.[21] Por su parte, Plutarco, en el siglo II, nos informa de los nombres de los sacerdotes egipcios que habrían relatado a Solón la historia de la Atlántida: Sonkhis de Sais y Psenophis de Heliópolis.[22] Finalmente, en el siglo V, comentando el Timeo, Proclo refiere que Crantor (aprox. 340-290 a. C.), filósofo de la Academia platónica, viajó a Egipto y pudo ver las estelas en que se hallaba escrito el relato que escuchó Solón.[23] Otros autores antiguos y bizantinos como Teopompo,[24] Plinio,[25] Diodoro Sículo,[26] Claudio Eliano[27] y Eustacio,[28] entre otros, también hablan sobre la Atlántida, o los atlantes, o sobre una ignota civilización atlántica.

En el Renacimiento [editar]

Si bien conocida, durante la Edad Media la historia de la Atlántida no llamó mayormente la atención. En el Renacimiento, la leyenda fue recuperada por los humanistas, quienes la asumirán unas veces como vestigio de una sabiduría geográfica olvidada y otras, como símbolo de un porvenir utópico. El escritor mexicano Alfonso Reyes afirma que la Atlántida, así resucitada por los humanistas, trabajó por el descubrimiento de América.[29] Francisco López de Gómara en su Historia General de las Indias, de 1552, afirma que Colón pudo haber estado influido por la leyenda atlántida y ve en voz náhuatl atl (agua) un indicio de vínculo entre aztecas y atlantes.[30] Duante los siglos XVI y XVII, varias islas (Azores, Canarias, Antillas, etc.) figuraron en los mapas como restos del continente perdido. En 1626, el filósofo inglés Francis Bacon publica La Nueva Atlántida (The New Atlantis), delirante utopía en pro de un mundo basado en los principios de la razón y el progreso científico y técnico. En España, en 1673, el cronista José Pellicer de Ossau identifica la Atlántida con la península Ibérica, asociando a los atlantes con los misteriosos tartessios.[31]

La obra de Ignatius Donnelly [editar]

No será hasta la segunda mitad del siglo XIX, que la historia de la Atlántida adquiera la fascinación que provoca hasta hoy en día. En 1869, Julio Verne escribe Veinte mil leguas de viaje submarino, novela que en su capítulo IX describe un alucinante encuentro de los protagonistas con los restos de una sumergida Atlántida. Tiempo después, en 1883, Ignatius Donnelly, congresista norteamericano, publica Atlántida: El Mundo Antediluviano (Atlantis: The Antediluvian World). En dicha obra, Donnelly, a partir de las semejanzas que aprecia entre las culturas egipcia y mesoamericana, hace converger, de modo muchas veces caprichoso, una serie de antecedentes y observaciones que lo llevan a concluir que hubo una región, desaparecida, que fue el origen de toda civilización humana (véase difusionismo) y cuyo eco habría perdurado en la leyenda de la Atlántida. El libro de Donnelly tuvo gran acogida de público (fue reeditado hasta 1976), en una época en que el avance de la ciencia permitía a su hipótesis aparecer seductoramente verosímil. Tanto fue así, que el gobierno británico organizó una expedición a las islas Azores, lugar donde el escritor situaba la Atlántida.[32]

La Atlántida después de Donnelly, hipótesis sobre la Atlántida en actualidad [editar]

La mayoría de las conjeturas que postulaban la existencia de la Atlántida como el "continente perdido", como la de Donnelly, fueron invalidadas por la comprobación del fenómeno de la deriva continental durante los años 1950. Por ello, algunas de las hipótesis modernas proponen que algunos de los elementos de la historia de Platón se derivan de mitos anteriores, o se refieren a lugares ya conocidos.

El éxito de Donnelly motivó a los autores más diversos a plantear sus propias teorías. En 1888, la ocultista Madame Blavatsky publica La Doctrina Secreta, texto basado, supuestamente, en un documento escrito en la Atlántida, El Libro de Dzian. Según Blavatsky, los atlantes habrían sido una raza de humanos anterior a la nuestra, cuya civilización habría alcanzado un notable desarrollo científico y espiritual. En 1938, el jerarca nazi Heinrich Himmler organiza, en el contexto del misticismo nacionalsocialista, una serie de expediciones a distintos lugares del mundo en busca de los antepasados atlantes de la raza aria. En 1940, el medium norteamericano Edgar Cayce predice que en 1968 la Atlántida volverá a la superficie frente a las costas de Florida. Sorprendentemente, en 1969, en las aguas de la isla de Bimini, frente a la península de Florida, será descubierta una formación rocosa a la que se dio el nombre de Carretera de Bimini, y respecto de la cual aún se discute si se trata o no de una construcción humana.

Al margen de lo esotérico, el impulso generado por la obra de Donnelly motivará también a numerosos historiadores y arqueólogos, tanto profesionales como aficionados, quienes durante el siglo XX desarrollarán teorías que ubicarán la Atlántida en los más distantes lugares, asociando a los atlantes con diferentes culturas de la Antigüedad. Es así como en 1913, el británico K. T. Frost sugiere, con poco éxito, que el imperio cretense, conocido de los egipcios, poderoso y posiblemente opresor de la Grecia primitiva, habría sido el antecedente fáctico de la leyenda atlántida.[33] La tesis de Frost, en un principio menospreciada, acabó convertirtiéndose en una teoría bastante aceptada y difundida. En 1938, el arqueólogo griego Spyridon Marinatos plantea que el fin la civilización cretense, a causa de la erupción del volcán de Santorini, podría ser el fondo histórico de la leyenda. La idea de Marinatos será trabajada por el sismólogo Angelos Galanopoulos, quien en 1960 publicará un artículo en donde sugerentemente relacionará la tesis cretense con los textos de Platón.[34] Si bien el propio Marinatos sostuvo siempre que se trataba de una simple especulación, la tesis de la Atlántida cretense ha tenido amplia aceptación y captado muchos seguidores, entre los que se contaba el ya fallecido oceanógrafo francés Jacques Cousteau.[35]

Por su parte, en 1922, el arqueólogo alemán Adolf Schulten retoma y populariza la idea de que Tartessos fue la Atlántida.[36] Tesis que cuenta con varios seguidores hasta el día de hoy. Otras hipótesis sobre la Atlántida la sitúan en la isla de Malta, el mar de Azov, los Andes en Sudamérica, el Próximo Oriente, el norte de África, Irlanda, Indonesia, el Sur de España y en la Antártida.

Sin embargo, ante la cantidad de sitios propuestos como el emplazamiento de la isla, algunos escépticos como Michael Shermer, fundador de la Skeptics Society,[37] y dueño de la revista Skeptic, sostiene que las hipótesis de la ubicación de la isla Atlántida tienen defectos de fondo y de forma. Tal y como es la tendencia más ampliamente aceptada desde las esferas científicas y académicas, Shermer propone que Platón realmente elabora un relato mítico con base en hechos y locaciones reales de la época.[38] Según Shermer, la historia de la Atlantida presenta un mensaje moral alrededor de una sociedad que al hacerse rica se torna belicosa y corrupta, y por ello es destruída por un castigo divino. Shermer rechaza en general todas las distintas teorías, y en particular el supuesto descubrimiento de la ubicación de la Atlántida en el sur de España por el investigador alemán Rainer Kühne;[39] y señala que el mito de la Atlántida propuesto por Platón recoje su percepción acerca del costo de la guerra en lo económico y social, derivado de su observación del conflicto armado entre los siracusanos y los cartagineses.

Falsa ubicación de la Atlántida en Google Maps

En febrero de 2009, el periódico Telegraph, del Reino Unido, "publicó un artículo insinuando que usando Google Ocean (una extensión de Google Earth) se podía ver un misterioso rectángulo cerca de las Islas Canarias, bajo el mar en las coordenadas . Inmediatamente, expertos y fanáticos de la Atlántida comenzaron a especular, asegurando que la imagen correspondía a la ciudad hundida. Google afirmó que la imagen corresponde a un típico error de procesamiento de imágen al momento que se recolectaron los datos de Batimetría de varios sonares de botes en la zona". [40]

Congresos sobre la Atlántida [editar]

En julio de 2005 se celebró en la isla griega de Milos el primer congreso de las hipótesis sobre la Atlántida,[41] donde los participantes expusieron sus tesis sobre la base histórico-geográfica del relato de la Atlántida reflejado en los diálogos de Platón. Como resultado del congreso, se elaboró una lista de 24 criterios para la localización de la Atlántida. Se convocó un segundo encuentro en Atenas en noviembre de 2008.[42] También se convocó un tercer congreso en Santorini para el año 2010.

La Atlántida en el arte y la cultura popular [editar]

En la República Oriental del Uruguay existe un balneario costero muy popular denominado Atlántida.

En la literatura [editar]

- Veinte mil leguas de viaje submarino (Vingt mille lieues sous les mers), de Julio Verne (1869): En el capítulo XI, el Nautilus visita las ruinas de la Atlántida.

- La Atlántida (L'Atlàntida), de Jacinto Verdaguer (1877): Poema clásico catalán que narra cómo Colón escucha de un ermitaño la historia de la Atlántida, luego de lo cual sueña con viajar a nuevas tierras.

- La Atlántida (L'Atlantide), de Pierre Benoît (1919): En una inexplorada región del Sahara, dos oficiales franceses descubren una fabulosa ciudad gobernada por una reina atlante.

- La Rebelión de Atlas (Atlas Shrugged) de Ayn Rand (1957): Describe un lugar llamado la Atlántida («Atlantis»), donde residen John Galt (el héroe de la novela) y sus amigos. Las referencias a Atlantis como símbolo de la sociedad propugnada por la filosofía objetivista, serán continuas en el resto de la carrera de Ayn Rand.

- Taliesin, de Stephen R. Lawhead (1987), primer volumen del Ciclo de Pendragon: El rey Avallach y su hija Charis, sobrevivientes de la Atlántida, llegan a las costas bretonas.

- Corazones en la Atlántida (Hearts in Atlantis), de Stephen King (1999): La Atlántida aparece como metáfora de la cultura popular de los años 60.

- El resurgir de la Atlántida (Raising Atlantis), de Thomas Greanias (2005): Un grupo de científicos, que investiga una inusual actividad sísmica en el polo sur, descubre la Atlántida.

- Ladrones de Atlántida, de José Ángel Muriel (2005): Un joven del antiguo Egipto debe sobrevivir en la Atlántida.

- Atlantis, de David Gibbins (2006): Un arqueólogo marino descubre indicios de la Atlántida en el Mar Mediterráneo.

- El Librero de la Atlántida, de Manuel Pimentel (2006): Un tímido librero, que escucha de un marinero historias sobre continentes perdidos, se enfrenta a la contingencia de un nuevo cambio climático, similar al que destruyó la Atlántida.

- El rey Kull el Conquistador, protagonista de una serie de relatos de Robert E. Howard, es un atlante que llega a convertirse en rey de Valusia, uno de los reinos de Atlantis.

- Atalantë («La Sepultada» en quenya, equivalente a Akallabêth en adunaico) es, en los relatos de J. R. R. Tolkien, el nombre que se da a la isla de Númenor, que Tolkien intencionadamente sitúa como símil de la Atlántida.

- El Códice de la Atlántida, una novela de Stel Pavlou (2007): De la Atlántida, asentamientos chinos, egipcios y mayas, sale una señal. La Humanidad ha tenido doce mil años para descifrar el mensaje. Ahora sólo queda una semana.

En la música [editar]

- Manuel de Falla puso música al poema de Jacinto Verdaguer, en una obra para solistas, coro y orquesta. La partitura, tras 20 años de trabajo, quedó truncada por la muerte de su autor en 1946. Su discípulo Ernesto Halffter la completó, estrenándola en 1976.

- El Grupo de Power Metal Stratovarius titula Atlantis a una canción del disco Dreamspace

- EL Grupo de Pop, Prefab Sprout hizo una canción titulada Looking for Atlantis para el álbum Jordan: The Comeback.

- El dúo Modern Talking grabó la canción Atlantis is calling.

- El Grupo de Power Metal Tierra Santa con la canción Atlántida, en el álbum Legendario (1999).

- El disco Atylantos, the Legend of Atlantis, de Jean-Patric Capdevielle, es una ópera basada en la historia de la supuesta isla.

- El músico Mike Oldfield titula "Lament for Atlantis" un tema de su disco The Songs of Distant Earth (álbum) (1994).

- El grupo de Power Metal Arkania en su canción "Las Iras" de su disco "Espíritu irrompible".

- El Cantautor Dominicano Pavel Núñez, Compuso una canción a la que tituló Atlantis, en la que habla sobre un imperio en el fondo del mar con luz azul. Su segundo álbum obtiene su nombre por esta canción. Se inspiró mientras miraba la película animada de Disney acerca de esta Isla.

- EL grupo de Power Metal Iron Savior titula "Atlantis Falling" a una canción dentro de un álbum que lleva por nombre el mismo del grupo

En el cine [editar]

- El Continente Perdido (Atlantis, the Lost Continent), de George Pal (1961): Demetrios, un joven pescador de la antigua Grecia, se pierde en el mar y llega hasta las costas de la isla de Atlántida.[44]

- La Ciudad de Oro del Capitán Nemo (Captain Nemo and the Underwater City), de James Hill (1969).[45]

- Los Conquistadores de Atlantis (Warlords of Atlantis), de Kevin Connor (1978): Los atlantes actuales tratan de conquistar el mundo.[46]

- Los Depredadores del Abismo (Predatori di Atlantide), de Ruggero Deodato (1983): En las costas de Miami emerge la isla de Atlántida.[47]

- Atlantis: El Imperio Perdido (Atlantis: The Lost Empire), de Gary Trousdale y Kirk Wise (2001): Película de animación en que un joven científico y sus amigos buscan la Atlántida en Islandia.[48]

En el cómic [editar]

- Namor, el príncipe submarino, el más antiguo personaje de Marvel, es rey de Atlantis, reino sumergido de una raza de hombres capaces de respirar bajo el agua.

- Aquaman, de DC Comics, es también el rey de otra versión sumergida de Atlantis, esta vez habitada por sirenas.

- Lori Lemaris, por poco tiempo novia de Superman, es asimismo una habitante de la Atlántida.

- En Arion, Lord of Atlantis, se retrata la Atlántida como una avanzada civilización basada en la magia en vez de la ciencia.

- En El mal trago de Obélix, de la serie de cómics de Astérix y Obélix, se hace una visita a lo que queda de la Atlántida, en las Islas Canarias.

- En Orion, cómic de la editorial colombiana Cinco, el protagonista es un príncipe atlante.

- A través de "Norma Cómics" se publicó en 1991 "Indiana Jones y las Llaves de Atlantis" por Dan Barry. Relata las aventuras de Indiana Jones y Sophia Hapgood en su búsqueda de la Atlántida antes que los nazis. Datando de 1991 el cómic y el famoso videojuego "Indiana Jones and The Fate Of Atlantis" (con fecha de salida) 1992 el guión de ambos está casi a la par. Norma Editorial ha reeditado este cómic que se divide en 4 números (salieron entre mayo y septiembre de 1991)

En la televisión [editar]

- En la serie de ciencia-ficción Stargate Atlantis, Atlantis es una antigua ciudad creada por los antiguos, una avanzadísima y antigua raza de humanoides, que se autotrasladada desde la Tierra en naves espaciales creadas por ellos mismos por toda la Vía Láctea, extendiendo la raza humana por todos los planetas hasta llegar a la galaxia Pegaso y tras varias decenas de miles de años regresan.

- En Saint Seiya, este lugar es un inmenso Santuario dedicado a Poseidón, Dios de los Mares; se encuentra rodeado de siete enormes pilares que sujetan el océano encima de ellos y permite la vida en las profundidades. En el centro está el Pilar Central encima del Templo de Poseidón.

- En la serie de animación japonesa, La Visión de Escaflowne, Atlantis se desarrolló en la Tierra, alcanzando un grado de tecnología que era posible materializar los deseos, de tal forma que se hicieron a sí mismos, seres hermosos y alados. Sin embargo, Atlantis desapareció, presumiblemente, por deseo de los propios Atlantes, y se trasladó todo su reino a Gaia, el mundo donde se desarrolla la serie, donde fueron llamados los Ryu-jin (gente dragón), pero ahí no alcanzaron la paz, y una guerra civil llevó a la destrucción del reino, por lo que los Ryu-jin serían considerados malditos.

- En un capítulo de Bob Esponja, Bob y compañía viajan a la Atlántida por medio de un autobús.

- En Yu Gi Oh! Waking of Dragons, toda la trama está basada en la mitología atlante.

- En la serie de animada Fushigi no umi no Nadia, su personaje principal Nadia es descendiente de los habitantes de la antigua Atlántida.

- En Las Aventuras de Jackie Chan segunda temporada, Bai - Tsa, el demonio del agua buscaba reconstruir la antigua Atlántida.

- En Los Padrinos Mágicos la Atlantis fue hundida por Cosmo

En los videojuegos [editar]

- En la aventura gráfica Indiana Jones and the Fate of Atlantis, Indiana Jones y la médium Sophia Hapgood buscan y llegan hasta la Atlántida, que el juego sitúa en el Mediterráneo, con las islas de Thera (hoy Santorini) y Creta como colonias menor y mayor del antiguo imperio. En el juego, destacan sobremanera la ambientación y el cuidadoso estudio de las civilizaciones de la Edad del Bronce, para dar a Atlantis un marcado sabor minoico.

- El éxito mundial del juego de estrategia Age of Mythology llevó a Ensemble Studios a crear una expansión de éste, la cual sería bautizada con el nombre de Age of Mythology: The Titans, que incluye como nueva cultura a la Atlántida

- También aparece en Tomb Raider el Sción como tema principal de la trama del juego.

- Aventura gráfica 3D de los estudios CRYO: Atlantis: the lost tales.

- La expansión del juego que creó Sierra Entertainment titulada Señor de la Atlántida - Poseidón, como continuación de Zeus: Señor del Olimpo.

- En Golden Sun, Golden Sun The Lost Age de Game Boy Advance, también se hace referencia a la Atlántida y la famosa Lemuria.

- En el videojuego de lucha Eternal Champions de Sega, el personaje de Trident es el príncipe de Atlantis.

- En el videojuego Madden 08 sale un equipo llamado Tridents, que representan a la Atlántida con los nombres de los jugadores como "Poseidón", y su estadio se localiza en la Atlántida.

- Existe para PSONE,el videojuego de la pelicula Atlantis: El Imperio Perdido (Atlantis: The Lost Empire)

- En el videjuego G.I. Joe: The Atlantis Factor, la Atlantida emerge del oceano y la organización Cobra la utiliza como su nueva base.

Bibliografía [editar]

Fuente secundaria [editar]

- Platón (2003). Diálogos. Volumen VI: Filebo. Timeo. Critias. Traducción, introducción y notas a cargo de Mª Ángeles Durán y Francisco Lisi. Madrid: Editorial Gredos ISBN 978-84-249-1475-2..

- — (2004). Diálogos. Ion. Timeo. Critias. Traducción, prólogo y notas de José María Pérez martel. Madrid: Alianza Editorial ISBN 978-84-206-5631-1..

Bibliografía analítica [editar]

- Ellis, Richard (2000). En Busca de la Atlántida. Grijalbo, Barcelona ISBN 84-253-3428-4..

- Vidal-Naquet, Pierre (2005). La Atlántida. Pequeña historia de un mito platónico. Akal, Madrid.

- Zamarro, Paulino (2001). Del estrecho de Gibraltar a la Atlántida. Edición propia, Madrid ISBN 84-87325-31-9..

Referencias y notas [editar]

- ↑ Timeo, 20d, 21d, 26e

- ↑ Timeo, 23e

- ↑ Timeo, 24e

- ↑ Critias, 118a-b

- ↑ Critias, 113 c

- ↑ Critias, 113d

- ↑ Critias, 113e-114a-c

- ↑ Critias, 114 b

- ↑ Critias, 114d-115a

- ↑ Critias, 115b

- ↑ Critias, 116d-e

- ↑ Critias, 115d-116a

- ↑ Critias, 118 c-e

- ↑ a b Critias, 119 d

- ↑ Critias, 120 b

- ↑ Critias, 120e, 121c

- ↑ Timeo, 25a-d

- ↑ Critias, 121a-c

- ↑ Timeo, 25e

- ↑ Estrabón, Geografía, II. 3.6

- ↑ Plinio el Viejo, Historia Natural, II. 92

- ↑ Plutarco, Solón, 26

- ↑ Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Timaeus, 1,76,1–2= FGrHist 665, F 31

- ↑ Teopompo, Theopompi Chii Fragmenta, collegit, disposuit, et explicavit, ejusdemque de Vita et Scriptis Commentationem praemisit. Lugduni Batavorum, 1829.

- ↑ Plinio, Plinio el Viejo, Historia Natural. Libro VI, XXXVI, 199.

- ↑ Diodoro Sículo, Diodorou Bibliotheke historike. Diodori Bibliotheca Historica. Ex recensione et cum annotationibus Ludovici Dindorfii. Ludwig August Dindorf. In aedibus B. G. Teubneri, 1866.

- ↑ Claudio Eliano, Aeliani De Animal. De Marinis Arietibus. Liber XV. Cap. 11. Edición utilizada: Eliano, Claudio: De historia animalium libri XVII, Lyon . 1562 . p. 424.

- ↑ Eustacio, Epistola de Conmentariis in Dionysium Periegeten. Eustathius Thessalonicensis". Geographi graeci minores. E codicibus recognovit prolegomenis annotatione indicibus instruxit tabulis aeri incisis illustravit". Carolus Müllerus (Karl Otfried Müller). Volumen secundum. Editore Ambrosio Firmin Didot, M DCCC LXI (1861); p. 256.

- ↑ Alfonso Reyes, "El presagio de América", Ultima Tule, O.C. t. XI: 11-62

- ↑ Francisco López de Gómara, Historia general de las Indias y conquista de México, CCXX, 1552

- ↑ José Pellicer de Ossau, Aparato A la Monarchia Antigva de las Españas En Los Tres Tiempos del Mvndo, El Adelon, El Mithico, y El Histórico, Valençia: Por Benito Macè, 1673

- ↑ Richard Ellis, En Busca de la Atlántida, p.55 y ss

- ↑ Frost, K. T., “The Critias and Minoan Crete”, in: Journal of Hellenic Studies 33, 1913, pp. 189–206

- ↑ Galanopoulos, Angelos, "On the Location and Side of Atlantis", in: Praktika Akademia Athen 35, 1960, pp 401-418

- ↑ Cousteau Society (1978), Cousteau Odyssey, Vol. 8: Calypso's Search for Atlantis (video), USA.

- ↑ Schulten, Adolf , “Tartessos and Atlantis”, in: Petermanns geographische Mitteilungen 73, 1927, pp. 284–288

- ↑ Sitio oficial de la Skeptic Society

- ↑ "La Atlántida, ¿Sólo un mito?"

- ↑ Noticias BBC: Científico dice que pudo haber descubierto los restos de la ciudad perdida de la Atlántida

- ↑ http://www.fayerwayer.com/2009/02/google-desmiente-que-imagen-en-google-earth-es-de-atlantida/all-comments/ Google desmiente que imagen en Google Earth es de Atlántida. Publicado el 23-2-2009 por Alexander Schek www.en fayerwayer.com

- ↑ «Hipótesis sobre la Atlántida»

- ↑ Página del evento

- ↑ celtiberia.net

- ↑ IMDb Atlantis, the Lost Continent

- ↑ IMDb Captain Nemo and the Underwater City

- ↑ IMDb Warlords of Atlantis

- ↑ IMDb Predatori di Atlantide

- ↑ IMDb Atlantis: The Last Empire

Véase también [editar]

Enlaces externos [editar]

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Atlántida.

Wikimedia Commons alberga contenido multimedia sobre Atlántida.

Textos de Platón sobre la Atlántida [editar]

Otros [editar]

Atlantis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Atlantis | |

|---|---|

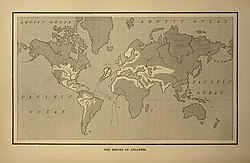

Athanasius Kircher's map of Atlantis, in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. From Mundus Subterraneus 1669, published in Amsterdam. The map is oriented with south at the top. | |

| Timaeus and Critias | |

| Creator | Plato |

| Type | Legendary island |

| Notable people | Atlanteans |

Atlantis (in Greek, Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, "island of Atlas") is a legendary island first mentioned in Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias.

In Plato's account, Atlantis was a naval power lying "in front of the Pillars of Hercules" that conquered many parts of Western Europe and Africa 9,000 years before the time of Solon, or approximately 9600 BC. After a failed attempt to invade Athens, Atlantis sank into the ocean "in a single day and night of misfortune".

Scholars dispute whether and how much Plato's story or account was inspired by older traditions. Some scholars argue Plato drew upon memories of past events such as the Thera eruption or the Trojan War, while others insist that he took inspiration from contemporary events like the destruction of Helike in 373 BC[1] or the failed Athenian invasion of Sicily in 415–413 BC.

The possible existence of a genuine Atlantis was discussed throughout classical antiquity, but it was usually rejected and occasionally parodied by later authors. As Alan Cameron states: "It is only in modern times that people have taken the Atlantis story seriously; no one did so in antiquity".[2] While little known during the Middle Ages, the story of Atlantis was rediscovered by Humanists in the Early Modern period. Plato's description inspired the utopian works of several Renaissance writers, like Francis Bacon's "New Atlantis". Atlantis inspires today's literature, from science fiction to comic books to films, its name having become a byword for any and all supposed advanced prehistoric lost civilizations.

Contents |

[edit] Plato's account

Plato's dialogues Timaeus and Critias, written in 360 BC, contain the earliest references to Atlantis. For unknown reasons, Plato never completed Critias; however, the scholar Benjamin Jowett, among others, argues that Plato originally planned a third dialogue titled Hermocrates. John V. Luce assumes that Plato, after describing the origin of the world and mankind in Timaeus and the allegorical perfect society of ancient Athens and its successful defense against an antagonistic Atlantis in Critias, would have made the strategy of the Greek civilization during their conflict with the Persians a subject of discussion in the Hermocrates. Plato introduced Atlantis in Timaeus:

For it is related in our records how once upon a time your State stayed the course of a mighty host, which, starting from a distant point in the Atlantic ocean, was insolently advancing to attack the whole of Europe, and Asia to boot. For the ocean there was at that time navigable; for in front of the mouth which you Greeks call, as you say, 'the pillars of Heracles,' there lay an island which was larger than Libya and Asia together; and it was possible for the travelers of that time to cross from it to the other islands, and from the islands to the whole of the continent over against them which encompasses that veritable ocean. For all that we have here, lying within the mouth of which we speak, is evidently a haven having a narrow entrance; but that yonder is a real ocean, and the land surrounding it may most rightly be called, in the fullest and truest sense, a continent. Now in this island of Atlantis there existed a confederation of kings, of great and marvelous power, which held sway over all the island, and over many other islands also and parts of the continent.[3]

The four persons appearing in those two dialogues are the politicians Critias and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus of Locri, although only Critias speaks of Atlantis. While most likely all of these people actually lived, these dialogues, written as if recorded, may have been the invention of Plato. In his works Plato makes extensive use of the Socratic dialogues in order to discuss contrary positions within the context of a supposition.

The Timaeus begins with an introduction, followed by an account of the creations and structure of the universe and ancient civilizations. In the introduction, Socrates muses about the perfect society, described in Plato's Republic (ca. 380 BC), and wonders if he and his guests might recollect a story which exemplifies such a society. Critias mentions an allegedly historical tale that would make the perfect example, and follows by describing Atlantis as is recorded in the Critias. In his account, ancient Athens seems to represent the "perfect society" and Atlantis its opponent, representing the very antithesis of the "perfect" traits described in the Republic. Critias claims that his accounts of ancient Athens and Atlantis stem from a visit to Egypt by the legendary Athenian lawgiver Solon in the 6th century BC. In Egypt, Solon met a priest of Sais, who translated the history of ancient Athens and Atlantis, recorded on papyri in Egyptian hieroglyphs, into Greek. According to Plutarch, Solon met with "Psenophis of Heliopolis, and Sonchis the Saite, the most learned of all the priests";[4] Plutarch refers here to events that would have happened five centuries before he wrote of them.

According to Critias, the Hellenic gods of old divided the land so that each god might own a lot; Poseidon was appropriately, and to his liking, bequeathed the island of Atlantis. The island was larger than Ancient Libya and Asia Minor combined,[5] but it afterwards was sunk by an earthquake and became an impassable mud shoal, inhibiting travel to any part of the ocean. The Egyptians, Plato asserted, described Atlantis as an island comprising mostly mountains in the northern portions and along the shore, and encompassing a great plain of an oblong shape in the south "extending in one direction three thousand stadia [about 555 km; 345 mi], but across the center inland it was two thousand stadia [about 370 km; 230 mi]." Fifty stadia [9 km; 6 mi] from the coast was a mountain that was low on all sides...broke it off all round about[6]... the central island itself was five stades in diameter [about 0.92 km; 0.57 mi].[7]

In Plato's myth, Poseidon fell in love with Cleito, the daughter of Evenor and Leucippe, who bore him five pairs of male twins. The eldest of these, Atlas, was made rightful king of the entire island and the ocean (called the Atlantic Ocean in his honor), and was given the mountain of his birth and the surrounding area as his fiefdom. Atlas's twin Gadeirus, or Eumelus in Greek, was given the extremity of the island towards the Pillars of Hercules.[8] The other four pairs of twins—Ampheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon, Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepes—were also given "rule over many men, and a large territory."

Poseidon carved the mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size. The Atlanteans then built bridges northward from the mountain, making a route to the rest of the island. They dug a great canal to the sea, and alongside the bridges carved tunnels into the rings of rock so that ships could pass into the city around the mountain; they carved docks from the rock walls of the moats. Every passage to the city was guarded by gates and towers, and a wall surrounded each of the city's rings. The walls were constructed of red, white and black rock quarried from the moats, and were covered with brass, tin and the precious metal orichalcum, respectively.[9]

According to Critias, 9,000 years before his lifetime a war took place between those outside the Pillars of Hercules at the Strait of Gibraltar and those who dwelt within them. The Atlanteans had conquered the parts of Libya within the Pillars of Hercules as far as Egypt and the European continent as far as Tyrrhenia, and subjected its people to slavery. The Athenians led an alliance of resistors against the Atlantean empire, and as the alliance disintegrated, prevailed alone against the empire, liberating the occupied lands.

But at a later time there occurred portentous earthquakes and floods, and one grievous day and night befell them, when the whole body of your warriors was swallowed up by the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner was swallowed up by the sea and vanished; wherefore also the ocean at that spot has now become impassable and unsearchable, being blocked up by the shoal mud which the island created as it settled down.[10]

[edit] Reception

[edit] Ancient

Other than Plato's Timaeus and Critias there is no primary ancient account of Atlantis, which means every other account of Atlantis relies on Plato in one way or another.

Some ancient writers viewed Atlantis as fiction while others believed it was real.[11] The philosopher Crantor, a student of Plato's student Xenocrates, is often cited as an example of a writer who thought the story to be historical fact. His work, a commentary on Plato's Timaeus, is lost, but Proclus, a Christian historian of the fifth century AD, reports on it.[12] The passage in question has been represented in the modern literature as both claiming that Crantor actually visited Egypt and had conversations with priests and saw hieroglyphs confirming the story, or as learning about them from other visitors to Egypt.[13] Proclus wrote

As for the whole of this account of the Atlanteans, some say that it is unadorned history, such as Crantor, the first commentator on Plato. Crantor also says that Plato's contemporaries used to criticize him jokingly for not being the inventor of his Republic but copying the institutions of the Egyptians. Plato took these critics seriously enough to assign to the Egyptians this story about the Athenians and Atlanteans, so as to make them say that the Athenians really once lived according to that system.

The next sentence is often translated as Crantor adds, that this is testified by the prophets of the Egyptians, who assert that these particulars [which are narrated by Plato] are written on pillars which are still preserved. But in the original, the sentence starts not with the name Crantor but with the word 'He', and whether this referred to Crantor or Plato is the subject of considerable debate. Proponents of both Atlantis as a myth and Atlantis as history have argued that the word should be translated as Crantor[14] Alan Cameron argues that it should be interpreted as 'Plato', and that when Proclus writes we must bear in mind concerning this whole feat of the Athenians, that it is neither a mere myth nor unadorned history, although some take it as history and others as myth... he is treating "Crantor's view as mere personal opinion, nothing more; in fact he first quotes and then dismisses it as representing one of the two unacceptable extremes."[15] Cameron also points out that whether 'he' refers to Plato or Crantor, it does not support statements such as Otto Muck's "Crantor came to Sais and saw there in the temple of Neith the column, completely covered with hieroglyphs, on which the history of Atlantis was recorded. Scholars translated it for him, and he testified that their account fully agreed with Plato's account of Atlantis...." or J.V. Luce's suggestion that Crantor sent "a special enquiry to Egypt" and that he may simply be referring to Plato's own claims.[15]

Another passage from Proclus' commentary on the Timaeus gives a description of the geography of Atlantis: "That an island of such nature and size once existed is evident from what is said by certain authors who investigated the things around the outer sea. For according to them, there were seven islands in that sea in their time, sacred to Persephone, and also three others of enormous size, one of which was sacred to Pluto, another to Ammon, and another one between them to Poseidon, the extent of which was a thousand stadia [200 km]; and the inhabitants of it—they add—preserved the remembrance from their ancestors of the immeasurably large island of Atlantis which had really existed there and which for many ages had reigned over all islands in the Atlantic sea and which itself had like-wise been sacred to Poseidon. Now these things Marcellus has written in his Aethiopica".[16] Marcellus remains unidentified.

Other ancient historians and philosophers believing in the existence of Atlantis were Strabo and Posidonius.[17]

Plato's account of Atlantis may have also inspired parodic imitation: writing only a few decades after the Timaeus and Critias, the historian Theopompus of Chios wrote of a land beyond the ocean known as Meropis. This description was included in Book 8 of his voluminous Philippica, which contains a dialogue between King Midas and Silenus, a companion of Dionysus. Silenus describes the Meropids, a race of men who grow to twice normal size, and inhabit two cities on the island of Meropis (Cos?): Eusebes (Εὐσεβής, "Pious-town") and Machimos (Μάχιμος, "Fighting-town"). He also reports that an army of ten million soldiers crossed the ocean to conquer Hyperborea, but abandoned this proposal when they realized that the Hyperboreans were the luckiest people on earth. Heinz-Günther Nesselrath has argued that these and other details of Silenus' story are meant as imitation and exaggeration of the Atlantis story, for the purpose of exposing Plato's ideas to ridicule.[18]

Zoticus, a Neoplatonist philosopher of the 3rd century AD, wrote an epic poem based on Plato's account of Atlantis.[19]

The 4th century AD historian Ammianus Marcellinus, relying on a lost work by Timagenes, a historian writing in the 1st century BC, writes that the Druids of Gaul said that part of the inhabitants of Gaul had migrated there from distant islands. Some have understood Ammianus's testimony as a claim that at the time of Atlantis's actual sinking into the sea, its inhabitants fled to western Europe; but Ammianus in fact says that “the Drasidae (Druids) recall that a part of the population is indigenous but others also migrated in from islands and lands beyond the Rhine" (Res Gestae 15.9), an indication that the immigrants came to Gaul from the north (Britain, the Netherlands or Germany), not from a theorized location in the Atlantic Ocean to the south-west.[20] Instead, the Celts that dwelled along the ocean were reported to venerate twin gods (Dioscori) that appeared to them coming from that ocean.[21]

A Hebrew treatise on computational astronomy dated to AD 1378/79, alludes to the Atlantis myth in a discussion concerning the determination of zero points for the calculation of longitude:

Some say that they [the inhabited regions] begin at the beginning of the western ocean [the Atlantic] and beyond. For in the earliest times [literally: the first days] there was an island in the middle of the ocean. There were scholars there, who isolated themselves in [the pursuit of] philosophy. In their day, that was the [beginning for measuring] the longitude[s] of the inhabited world. Today, it has become [covered by the?] sea, and it is ten degrees into the sea; and they reckon the beginning of longitude from the beginning of the western sea.[22]

[edit] Modern

Francis Bacon's 1627 essay The New Atlantis describes a utopian society that he called Bensalem, located off the western coast of America. A character in the narrative gives a history of Atlantis that is similar to Plato's and places Atlantis in America. It is not clear whether Bacon means North or South America. Isaac Newton's 1728 The Chronology of the Ancient Kingdoms Amended studies a variety of mythological links to Atlantis.[23] In the middle and late 19th century, several renowned Mesoamerican scholars, starting with Charles Etienne Brasseur de Bourbourg, and including Edward Herbert Thompson and Augustus Le Plongeon proposed that Atlantis was somehow related to Mayan and Aztec culture. The 1882 publication of Atlantis: the Antediluvian World by Ignatius L. Donnelly stimulated much popular interest in Atlantis. Donnelly took Plato's account of Atlantis seriously and attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations were descended from its high Neolithic culture.

During the late 19th century, ideas about the legendary nature of Atlantis were combined with stories of other lost continents such as Mu and Lemuria. Helena Blavatsky wrote in The Secret Doctrine that the Atlanteans were cultural heroes (contrary to Plato who describes them mainly as a military threat), and are the fourth "Root Race", succeeded by the "Aryan race". Theosophists believe the civilization of Atlantis reached its peak between 1,000,000 and 900,000 years ago but destroyed itself through internal warfare brought about by the inhabitants' dangerous use of magical powers. Rudolf Steiner wrote of the cultural evolution of Atlantis[citation needed] in much the same vein. Edgar Cayce first mentioned Atlantis in 1923,[24] and later suggested that it was originally a continent-sized region extending from the Azores to the Bahamas, holding an ancient, highly evolved civilization which had ships and aircraft powered by a mysterious form of energy crystal. He also predicted that parts of Atlantis would rise in 1968 or 1969. The Bimini Road, a submerged rock formation of large rectangular stones just off North Bimini Island in the Bahamas, was claimed by Robert Ferro and Michael Grumley[25] to be evidence of the lost civilization.

According to Herodotus (c. 430 BC), a Phoenician expedition had circumnavigated Africa at the behest of pharaoh Necho, sailing south down the Red Sea and Indian Ocean and northwards in the Atlantic, re-entering the Mediterranean Sea through the Pillars of Hercules. His description of northwest Africa makes it very clear that he located the Pillars of Hercules precisely where they are located today. Nevertheless, a supposed belief that they had been placed at the Strait of Sicily prior to Eratosthenes, has been cited in some Atlantis theories.

[edit] In Nazi mysticism

The concept of Atlantis attracted Nazi theorists. In 1938, SS Officer Heinrich Himmler organized a German expedition to Tibet in 1939 to search for Aryan Atlanteans[citation needed], although this suggestion has been criticised as inaccurate[26] and that the expedition was looking for the origins of the 'Europid' race or that it was a more general biological expedition[27]. According to Julius Evola, writing in 1934,[28] the Atlanteans were Hyperboreans—Nordic supermen who originated on the North pole (see Thule). Similarly, Alfred Rosenberg (The Myth of the Twentieth Century, 1930) spoke of a "Nordic-Atlantean" or "Aryan-Nordic" master race.

[edit] Recent times

As continental drift became more widely accepted during the 1960s, and the increased understanding of plate tectonics demonstrated the impossibility of a lost continent in the geologically recent past, most “Lost Continent” theories of Atlantis began to wane in popularity. Instead, the fictional nature of elements of Plato's story became widely emphasized.

Plato scholar Dr. Julia Annas, Regents Professor of Philosophy at the University of Arizona, has had this to say on the matter:

The continuing industry of discovering Atlantis illustrates the dangers of reading Plato. For he is clearly using what has become a standard device of fiction—stressing the historicity of an event (and the discovery of hitherto unknown authorities) as an indication that what follows is fiction. The idea is that we should use the story to examine our ideas of government and power. We have missed the point if instead of thinking about these issues we go off exploring the sea bed. The continuing misunderstanding of Plato as historian here enables us to see why his distrust of imaginative writing is sometimes justified.[29]

Kenneth Feder points out that Critias's story in the Timaeus provides a major clue. In the dialogue, Critias says, referring to Socrates' hypothetical society:

And when you were speaking yesterday about your city and citizens, the tale which I have just been repeating to you came into my mind, and I remarked with astonishment how, by some mysterious coincidence, you agreed in almost every particular with the narrative of Solon. ...[30]

Feder quotes A. E. Taylor, who wrote, "We could not be told much more plainly that the whole narrative of Solon's conversation with the priests and his intention of writing the poem about Atlantis are an invention of Plato's fancy."[31]

[edit] Location hypotheses

Since Donnelly's day, there have been dozens of locations proposed for Atlantis, to the point where the name has become a generic concept, divorced from the specifics of Plato's account. This is reflected in the fact that many proposed sites are not within the Atlantic at all. Few today are scholarly or archaeological hypotheses, while others have been made by psychic or other pseudoscientific means. Many of the proposed sites share some of the characteristics of the Atlantis story (water, catastrophic end, relevant time period), but none has been demonstrated to be a true historical Atlantis.

[edit] In or near the Mediterranean Sea

Most of the historically proposed locations are in or near the Mediterranean Sea: islands such as Sardinia, Crete and Santorini, Sicily, Cyprus, and Malta; land-based cities or states such as Troy, Tartessos, and Tantalus (in the province of Manisa), Turkey; and Israel-Sinai or Canaan.[citation needed] The Thera eruption, dated to the 17th or 16th century BC, caused a large tsunami that experts hypothesize devastated the Minoan civilization on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the story.[32] A. G. Galanopoulos argued that the time scale has been distorted by an error in translation, probably from Egyptian into Greek, which produced "thousands" instead of "hundreds"; this same error would rescale Plato's Kingdom of Atlantis to the size of Crete, while leaving the city the size of the crater on Thera; 900 years before Solon would be the 15th century BC.[33] In the area of the Black Sea the following locations have been proposed: Bosporus and Ancomah (a legendary place near Trabzon). The Sea of Azov was proposed in 2003.[34]

[edit] In the Atlantic Ocean

The location of Atlantis in the Atlantic Ocean has certain appeal given the closely related names. Popular culture often places Atlantis there, perpetuating the original Platonic setting. Several hypotheses place the sunken island in northern Europe, including Sweden (by Olof Rudbeck in Atland, 1672–1702), or in the North Sea. Some have proposed the Celtic Shelf and Andalusia as possible locations, and that there is a link to Ireland.[35] The Canary Islands have also been identified as a possible location, west of the Straits of Gibraltar but in proximity to the Mediterranean Sea. Various islands or island groups in the Atlantic were also identified as possible locations, notably the Azores. However detailed geological studies of the Canary Islands, the Azores, and the ocean bottom surrounding them found a complete lack of any evidence for the catastrophic subsidence of these islands at any time during their existence and a complete lack of any evidence that the ocean bottom surrounding them was ever dry land at any time in the past.[36] The submerged island of Spartel near the Strait of Gibraltar has also been suggested.[37]

[edit] Other locations

Caribbean locations such as Cuba, the Bahamas, and the Bermuda Triangle[38] have been proposed as sites of Atlantis. Areas in the Pacific and Indian Oceans have also been proposed including Indonesia, Malaysia or both (i.e. Sundaland) and stories of a lost continent off India named "Kumari Kandam" have inspired some to draw parallels to Atlantis, as has the Yonaguni Monument of Japan. Antarctica has also been suggested.

[edit] Art, literature and popular culture

The legend of Atlantis is featured in many books, films, television series, games, songs and other creative works. Recent examples of Atlantis on-screen include the television series Stargate Atlantis and the Disney animated film Atlantis: The Lost Empire. The first Tomb Raider video game features Atlantis as the basis of its plot and the location for its climactic ending. It is also featured prominently and somewhat philosophically in Robert Anton Wilson and Robert Shea's The Illuminatus! Trilogy, and is a staple of New Age philosophies.

[edit] Notes

- ^ Plato's Timaeus is usually dated 360 BC; it was followed by his Critias.

- ^ Alan Cameron, Greek Mythography in the Roman World, Oxford University Press (2004) p. 124

- ^ Timaeus 24e–25a, R. G. Bury translation (Loeb Classical Library).

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Solon.

- ^ Atlantis—Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Critias 113, Bury translation.

- ^ Critias 116a, Bury translation.

- ^ The name is a back-formation from Gades, the Greek name for Cadiz.

- ^ Critias 116bc

- ^ Timaeus 25c–d, Bury translation.

- ^ Nesselrath (2005), pp. 161–171.

- ^ Timaeus 24a: τὰ γράμματα λαβόντες.

- ^ Cameron 2002

- ^ Castleden 2001, p,168

- ^ a b Cameron 1983

- ^ Proclus, Commentary on Plato's Timaeus, p. 117.10–30 (=FGrHist 671 F 1), trans. Taylor, Nesselrath).

- ^ Strabo 2.3.6

- ^ Nesselrath 1998, pp. 1–8.

- ^ Porphyry, Life of Plotinus, 7=35.

- ^ Fitzpatrick-Matthews, Keith. Lost Continents: Atlantis.

- ^ [1] Bibliotheca historica - Diodorus Siculus 4.56.4: "And the writers even offer proofs of these things, pointing out that the Celts who dwell along the ocean venerate the Dioscori above any of the gods, since they have a tradition handed down from ancient times that these gods appeared among them coming from the ocean. Moreover, the country which skirts the ocean bears, they say, not a few names which are derived from the Argonauts and the Dioscori."

- ^ Selin, Helaine 2000, Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astronomy, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands, pg 574. ISBN 0-7923-6363-9

- ^ Isaac Newton (1728). The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended

- ^ Robinson, Lytle, 1972, Edgar Cayce’s Story of the Origin and Destiny of Man, Berkeley Books, New York, pg 51.

- ^ Ferro and Grumley, Atlantis: the Autobiography of a Search (New York: Doubleday) 1970.

- ^ Fortean Times, October 2003, Christopher Hale, Page 31

- ^ Fortean Times, October 2003, Christopher Hale, Page 38

- ^ Evola, Revolt Against the Modern World, 1934.

- ^ J. Annas, Plato: A Very Short Introduction (OUP 2003), p.42 (emphasis not in the original)

- ^ Timaeus 25e, Jowett translation.

- ^ Feder, Kenneth L., Frauds, Myths and Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology, Mayfield Publishing, 1999, p. 164.

- ^ The wave that destroyed Atlantis Harvey Lilley, BBC News Online, 2007-04-20. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ^ Galanopoulos, Angelos Geōrgiou, and Edward Bacon, Atlantis: The Truth Behind the Legend, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1969

- ^ Eagle, Wind, Atlantis Motherland, Maui, HI: Cosmic Vortex, 2003 ISBN 0-9719580-0-9

- ^ Lovgren, Stefan (2004-08-19). "Atlantis "Evidence" Found in Spain and Ireland". National Geographic. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/08/0819_040819_atlantis.html. Retrieved 2007-12-05.

- ^ Location hypotheses of Atlantis

- ^ http://antiquity.ac.uk/ProjGall/kuhne/ A location for "Atlantis"? Rainer W. Kühne Antiquity Vol 78 No 300 June 2004

- ^ Hanson, Bill. The Atlantis Triangle. 2003.

[edit] Further reading

[edit] Ancient sources

- Plato, Timaeus, translated by Benjamin Jowett at Project Gutenberg; alternative version with commentary.

- Plato, Critias, translated by Benjamin Jowett at Project Gutenberg; alternative version with commentary.

[edit] Modern sources

- Bichler, R (1986). 'Athen besiegt Atlantis. Eine Studie über den Ursprung der Staatsutopie', Canopus, vol. 20, no. 51, pp. 71–88.

- Cameron, Alan (1983). 'Crantor and Posidonius on Atlantis', The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 33, No. 1 (1983), pp. 81–91

- Cayce, Edgar Evans (1968). Edgar Cayce's Atlantis. ISBN 9780876045121

- Crowley, Aleister - Lost Continent

- De Camp, LS (1954). Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature, New York: Gnome Press.

- Castleden, Rodney (2001) Atlantis Destroyed', London:Routledge

- Donnelly, I (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved November 6, 2001, from Project Gutenberg.

- Ellis, R (1998). Imaging Atlantis, New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-679-44602-8

- Erlingsson, U (2004). Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land, Miami: Lindorm. ISBN 0-9755946-0-5

- Flem-Ath R, Wilson C (2001). The Atlantis Blueprint: Unlocking the Ancient Mysteries of a Long-Lost Civilization, Delacorte Press

- Frau, S (2002). Le Colonne d'Ercole: Un'inchiesta, Rome: Nur neon. ISBN 88-900740-0-0

- Gill, C (1976). 'The origin of the Atlantis myth', Trivium, vol. 11, pp. 8–9.

- Gordon, J.S. (2008). 'The Rise and Fall of Atlantis: and the mysterious origins of human civilization', Watkins Publishing, London. ISBN 978-1-905857-24-1

- Görgemanns, H (2000). 'Wahrheit und Fiktion in Platons Atlantis-Erzählung', Hermes, vol. 128, pp. 405–420.

- Griffiths, JP (1985). 'Atlantis and Egypt', Historia, vol. 34, pp. 35f.

- Heidel, WA (1933). 'A suggestion concerning Platon's Atlantis', Daedalus, vol. 68, pp. 189–228.

- Jakovljevic, Ranko (2005) Gvozdena vrata Atlantide, IK Beoknjiga Belgrade. ISBN 86-7694-042-8

- Jakovljevic, Ranko (2008) Atlantida u Srbiji IK Pesic i sinovi Belgrade. ISBN 978-86-7540-091-2

- Jordan, P (1994). The Atlantis Syndrome, Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3518-9

- King, D. (1970). Finding Atlantis: A true story of genius, madness, and an extraordinary quest for a lost world. Harmony Books, New York. ISBN 1-4000-4752-8

- Luce, J V (1982). End of Atlantis: New Light on an Old Legend, Efstathiadis Group: Greece

- Martin, TH [1841] (1981). 'Dissertation sur l'Atlantide', in TH Martin, Études sur le Timée de Platon, Paris: Librairie philosophique J. Vrin, pp. 257–332.

- Morgan, KA (1998). 'Designer history: Plato's Atlantis story and fourth-century ideology', Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 118, pp. 101–118.

- Muck, Otto Heinrich, The Secret of Atlantis, Translation by Fred Bradley of Alles über Atlantis (Econ Verlag GmbH, Düsseldorf-Wien, 1976), Times Books, a division of Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co., Inc., Three Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016, 1978

- Nesselrath, HG (1998). 'Theopomps Meropis und Platon: Nachahmung und Parodie', Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft, vol. 1, pp. 1–8.

- Nesselrath, HG (2001a). 'Atlantes und Atlantioi: Von Platon zu Dionysios Skytobrachion', Philologus, vol. 145, pp. 34–38.

- Nesselrath, HG (2001b). 'Atlantis auf ägyptischen Stelen? Der Philosoph Krantor als Epigraphiker', Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, vol. 135, pp. 33–35.

- Nesselrath, HG (2002). Platon und die Erfindung von Atlantis, München/Leipzig: KG Saur Verlag. ISBN 3-598-77560-1

- Nesselrath, HG (2005). 'Where the Lord of the Sea Grants Passage to Sailors through the Deep-blue Mere no More: The Greeks and the Western Seas', Greece & Rome, vol. 52, pp. 153–171.

- Phillips, ED (1968). 'Historical Elements in the Myth of Atlantis', Euphrosyne, vol. 2, pp. 3–38

- Ramage, ES (1978). Atlantis: Fact or Fiction?, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-10482-3

- Settegast, M. (1987). Plato Prehistorian: 10,000 to 5000 B.C. in Myth and Archaeology, Cambridge, MA, Rotenberg Press.

- Spence, L [1926] (2003). The History of Atlantis, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-42710-2

- Stiebing, William H., Jr. (1984). Ancient Astronauts, Cosmic Collisions and Other Popular Theories about Man's Past. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 0-87975-285-8..

- Szlezák, TA (1993). 'Atlantis und Troia, Platon und Homer: Bemerkungen zum Wahrheitsanspruch des Atlantis-Mythos', Studia Troica, vol. 3, pp. 233–237.

- Vidal-Naquet, P (1986). 'Athens and Atlantis: Structure and Meaning of a Platonic Myth', in P Vidal-Naquet, The Black Hunter, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 263–284. ISBN 0-8018-3251-9

- Wilson, Colin (1996). From Atlantis to the Sphinx ISBN 1-85227-526-X

- Zangger, E (1993). The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis legend, New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-11350-8

- Zhirov, Nikolai F., Atlantis – Atlantology: Basic Problems, Translated from the Russian by David Skvirsky, Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1970

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Atlantis |

| Look up atlantis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| | ||

|---|---|---|

| Category: Greek Mythology | A - Amp | Amp - Az | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q- R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z Greek Mythology stub | Ab - Al | Ale - Ant | Ant - Az | B | C | D | E | F - G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q - R | R | S | T | A - K | L - Z Category:Greek deity stubs (593)EA2 | A | B | C | D | E | G | H | I | K | L | M | N | O | P | S | T | U | Z | ||

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario